Are you going for a hike? Don’t forget your bottle of ant musk.

A new scientific study suggests that some species of ticks—those Lyme Disease-spreading creepy crawlies—are scared off by pheromones produced by ants. Now, a team of researchers is working to synthetically replicate these ant excretions and sell them as tick repellent. Because unlike DEET or Citronella or other popular tick spray, the one derived from ant juice is virtually undetectable by the human nose.

“The ant deposits do not have a noticeable odor—the synthetic pheromones have an acidic odor similar to vinegar but only at high concentrations,” said Claire Gooding, the lead author of the study. “At the concentrations deterrent to ticks, the odor is not noticeable.”

In January, Gooding and her team of scientists at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, British Columbia, published a report in Royal Society Open Science about their research project on black-legged ticks. The group set out to examine how the ticks avoid being eaten by their everyday predators, specifically ants, spiders, and beetles. They realized that the blood-sucking insects detect chemicals left by their enemies, and retreat when they smell them.

Researchers eventually focused their study on pheromones produced by ants, because many species of ant produce a wide range of excretions—a definition that scientists call “chemically noisy,” Gooding said.

“We decided to look at ants because they are social insects and use a huge range of pheromones to communicate with one another,” says Gooding. “And for something that perceives the world chemically, they’re easy to predict where they’ll be, based on these pheromones.”

Scientists placed solitary ticks into a glass enclosure that consisted of three aligned chambers connected by tunnel-like tubes. They then placed filter paper treated with different ant pheromones in one of the chambers, and examined whether or not the tick moved through the tunnels into the chamber furthest from the chemically-treated paper.

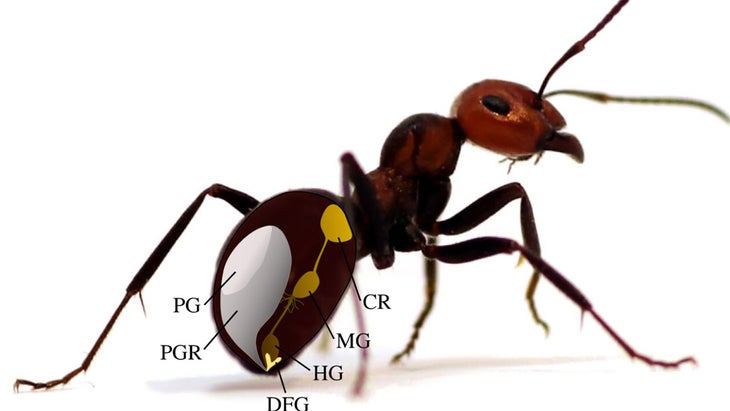

Once researchers determined which chemicals deterred the ticks, they then had to locate the specific pheromone-producing glands inside an ant. A common ant has multiple glands in its abdomen, and each one secrets a different mixture of chemicals. For each test researchers had to freeze worker ants and then dissect them. After some trial and error, researchers determined that the pheromones produced in an ant’s Dufour and poison glands had the highest success rate at scaring off ticks.

“They could see that there were ants and basically go, ‘I’m not going to go there, because there may be ants there, or there may be ants there again soon in the future,’” Gooding said.

Gooding and her peers then worked with a team of chemists in Vancouver to produce synthetic versions of the pheromones. The man-made ant scents also caused ticks to retreat.

Gooding said that the synthetically-produced ant pheromones could someday be used in spray-on repellents, or they could be added to wood chips or other materials to create environmental barriers for ticks.

There’s no definitive timeline for when tick spray containing synthetic ant pheromones will hit store shelves, Gooding said. The group has filed a provisional patent in Canada and is working with industrial sponsors to eventually sell the concoction. “We are optimistic that, with further testing to ensure safety and efficacy, our findings can be developed into a usable product,” she said. “We are also looking into whether ant pheromones can be combined with other repellent compounds to create an even more effective repellent.”

Alas, hikers won’t be the first warm-blooded animals to douse themselves in ant pheromones to ward off vermin. Some species of birds commonly rub dead ants on their plumage, while others simply land on ant colonies and invite the insects to climb all of them. Researchers and birdwatchers call this practice “anting,” and some believe it wards off mites and some forms of fungi.