Alex Kapranos has been consumed by fear of late. Nothing too terrible. “The fear of non-existence. The fear of a futile life. The fear of losing people you love. If you have periods of solitude and introspection, it’s easy to let them dominate your thoughts,” he says, looking more eager than anxious on a Zoom call from his adopted Parisian home.

The theme surprised him when he looked back at the songs he’d written for his new record. Amid his various creative pursuits – radio broadcasting, sound production, film narration, furniture carpentry, sundry collaborations – it’s the sixth by Franz Ferdinand, the synth-guitar band he took from Glasgow to the world 20 years ago.

“Each song had a different fear underlying it, whether it was the fear of committing to a relationship or breaking a relationship or the fear of leaving an institution or the fear of being rejected by your peers,” he says.

“I thought, ‘Oh that’s cool’, and it’s also fascinating because fear is what makes us human as well. We all have these fears, but how we respond to those fears depends on our character, our personality. It’s how we find out who we are.”

The title track of The Human Fear is his response to laying eyes on his firstborn. He prefers to identify his 16-month-old son by the codename “G”, to protect him from the tabloid lens that routinely attends his wife, French singer-songwriter Clara Luciani.

“When he was born, when the waters broke … these emotional waters broke in me and I was overwhelmed by a certain sensation of love which was kind of unfamiliar,” Kapranos says. “After the shock of that subsided, I realised that those fears were still there, but they felt kind of insignificant or trivial in comparison.”

The response pattern he identified in himself is defined in the album’s first song, Audacious. In typical Franz style, the remedy for its bleak outlook of a world coming undone at the seams is a high-kicking feelgood chorus: “Don’t stop feeling audacious/ There’s no one to save us/So just carry on.”

Loading

“I’m probably quite a reckless person,” he says with a hint of mischief. “My wife is much more cautious than I am, and I think as parents, we balance each other out very well. Like, G’s got a little scooter bike thing he rides on, and I’m like, ‘What the hell you putting a f—ing helmet on him for? I spent years riding bikes without a helmet and my head’s fine!’”

Born near Bristol to a Greek father and English mother, Kapranos moved to Glasgow as a child and enjoyed an intriguingly unsettled career before success with Franz Ferdinand in his 30s. He’d been making albums at home since his teens, then spent the ’90s as a live music promoter and in various more-or-less experimental bands.

Take 7: The answers according to Alex Kapranos

- Worst habit? Cistercian.

- Greatest fear? Sticky surfaces.

- The line that stayed with you? The first is always most memorable, surely?

- Biggest regret? Never getting to have any regrets.

- Favourite book? What We Talk About When We Talk About Love by Raymond Carver.

- The artwork/song you wish was yours? I’m quite happy with the ones I have, thank you.

- If you could time travel, where would you go? Back three minutes to when I first made that crap joke about a monk’s habit so I could do it all over again.

Somewhere in between, plans to study philosophy in Glasgow went awry when he was accepted for a second choice he’d made by alphabetical selection: A for Aberdeen Uni, D for divinity. “Suddenly I found myself in freezing cold Aberdeen with a lot of guys in their 50s training to be ministers,” he says. “Quite an experience for 17-year-old me.

“I do like a bit of chaos in the order, definitely. Some of the most exciting things in my life have definitely come about through either chaos or doing the wrong thing, like misbehaving yourself, or being inappropriate in a particular place.

“I got into playing chess for a while, and I found what worked for me was to have a pattern to your playing which was really logical, and then if you felt you were in a stale situation, do the most illogical move you possibly could – just to mess it up, but also to freak out your opponent.”

The curveball on The Human Fear is a song called Black Eyelashes. Just as we’re feeling comfortable with the slick Anglo-indie-rock hooks that earned Franz Ferdinand their first Brit Awards in 2005, this one arrives like an unexpected continental relative: a daring dabble in the Greek urban music form rebetiko.

“One of the themes in rebetiko is either black eyebrows or black eyes or black eyelashes, and my eyes are blue. So it seems like a pretty good metaphor for me trying to find my Greek identity,” Kapranos says.

“I spent most of my life in Scotland but I’d go over to Greece all the time. My grandparents lived in Piraeus, and they would go, ‘Well, you look awfully blond for a Greek boy, and you don’t speak Greek.’

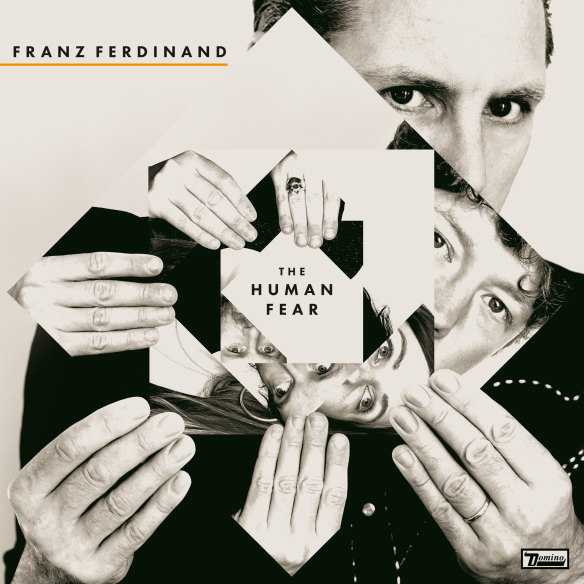

Alex Kapranos with his Franz Ferdinand bandmates.

“I guess I have the condition common to all children of immigrants, which is that I know where I’m from, but I also know that I’m not from there. I mean, I still have a bit of an English accent, but if I go back to England they think I’ve got a Scottish accent. In a wider sense, I guess I don’t feel like I belong anywhere. But I also feel like I belong in all of those places simultaneously.”

It’s a condition reflected in Kapranos’ other musical urges, which most recently included a bilingual Nancy Sinatra/Lee Hazlewood duet with his famous wife. In 2015, Franz joined forces with American cult electro duo Sparks for a project called FFS. In theory at least, Kapranos also remains a part of the trans-Atlantic supergroup BNQT.

“I do have other creative directions,” he says. “I like to write. I like my photography, music production and woodwork … My grandfather was a carpenter, so it’s always been a big part of my life.

“I think urge is the right word because to me that suggests something that is impossible to escape. An urge is something that can’t be ignored. An urge is something that almost controls you. You can’t have a life without it.

“I think more than anything it’s a sense of dissatisfaction. That’s a great motivator. Once you lose your sense of dissatisfaction, I think you lose yourself. You lose yourself as an artist once you feel like you’ve done your greatest work. When you become complacent, well, you become nothing.

“So yeah, I feel like maybe not having a sense of truly belonging helps you to feel dissatisfied. You feel like you’re always searching for a home that doesn’t really exist. That’s how I feel at the moment. I mean, I live in Paris now, and I can barely speak French. So I’m definitely continuing that tradition.”

The Human Fear by Franz Ferdinand is out now.