BBC

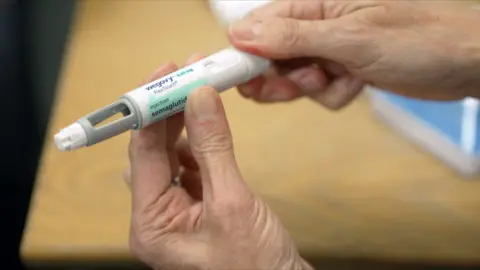

BBCRay, 62 from south London, became one of the first patients to receive the weight-loss jab Wegovy on the NHS last year and has lost 14kg (just over two stone) in five months.

BBC Panorama joined him as he was prescribed his first dose at London’s Guy’s Hospital, where he was told he would probably need to take the drug all his life to prevent him regaining weight. He said he felt “blessed” to be given the drug.

But the NHS spending watchdog NICE has ruled that each patient can only receive Wegovy for two years. And only a tiny proportion of the eligible 3.4 million patients in England are getting access to the drugs.

Prof Naveed Sattar, who leads the UK government’s Obesity Healthcare Goals programme, says if everyone eligible was given the drug right away “it would simply bankrupt the NHS”.

Being overweight is now the norm and nearly one in three adults in England is obese – double the rate of just 30 years ago.

Obesity can be very bad for your health, and treating the complications from it is estimated to cost the NHS across the UK more than £11bn a year.

Wegovy and another drug called Mounjaro can help patients lose about 15 to 20% of their bodyweight, according to trials.

That sort of weight loss can have a dramatic impact on health, and greatly reduce a patient’s risk of many conditions, from diabetes to cancer, joint problems and heart disease.

BBC Panorama has been given exclusive access to the weight management service at London’s Guy’s Hospital, which has begun rolling out Wegovy to a small group of patients who meet the criteria – a body mass index (BMI) of more than 35 and at least one weight-related health complication.

They include care home worker Ray, who weighed 148kg or 23 stone when he began taking Wegovy in July 2024. He has struggled with his weight all his life.

Ray needs two operations, but doctors have said he needs to lose weight first.

With so many patients meeting the criteria, the hospital is prioritising those like Ray who need surgery or who have multiple weight-related health complications.

Here, not only is Ray given the drug, which is taken via weekly injection under the skin, but he gets face-to-face support from doctors and dietitians – advice not always given to those buying the drug privately online.

They stress the jabs do not do all the work and it is important that patients change their lifestyle, and eat healthier food and smaller portions.

Ray is joined at the appointment by one of his daughters, Sophie, who says it would be “amazing” if he could reach his goal of losing three stone: “I wouldn’t recognise him. It would be like I have a brand new dad.”

For now, the drug is available on the NHS in England via these specialist services, mostly in hospitals.

But the chances of getting the drug are low.

Out of more than 130,000 patients eligible for weight-loss drugs in south-east London, the Guy’s clinic reckons it can only see about 3,000.

The weight-loss jab that most people know is Ozempic. It has been in huge demand and popularised by celebrities, from Elon Musk to Sharon Osbourne. In fact, it is meant to be for type 2 diabetes.

Wegovy contains the same ingredient, semaglutide, but in different dosages.

Semaglutide mimics a gut hormone that sends signals to our brain telling us we are full. It also slows the transit of food through the stomach.

In trials, patients on Wegovy lost an average of 15% body weight, when combined with lifestyle and dietary advice.

Experts warn the drugs should only be taken under proper medical supervision, because like all medicines they come with side effects, which not all patients can cope with.

These are mostly gastro-intestinal – such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea or constipation – but there are potentially serious complications including inflammation of the pancreas.

To help them cope with the side effects, patients are started on a low dose of the weight-loss jabs, and it is gradually increased, month by month.

Ray is doing well on the drug, eating smaller portions, and after five months there is a visible difference.

At his appointment at Guy’s just before Christmas, he weighs 134kg, a weight loss of 14kg or just over two stone.

He is delighted. “I can’t believe the amount of weight I’ve lost. Every time my daughters see me they say I’m shrinking. It’s been a really good journey.”

Ray says he feels “lucky” to have had access to the drug via the NHS, especially now he is a granddad to Willow.

Ray says despite putting many new holes in his belt, his trousers are so loose they are falling off him.

Prof Barbara McGowan, an expert in obesity and diabetes, who runs the weight management service at Guy’s is delighted with the progress of patients such as Ray.

She says most clinicians hope that NICE’s two-year limit will be removed “because obesity is a chronic disease and we need to manage it long-term”.

That may not be such an issue now that a second, even more effective drug has been approved by NICE (the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence).

Mounjaro has been dubbed the “King Kong” of weight-loss jabs as in a key trial, patients lost an average of 21% of bodyweight over eight months.

Unlike Wegovy, no restriction has been put on how long NHS patients can stay on the drug.

But the NHS is going to roll out the drug over 12 years because of concerns it could overwhelm services.

Over the next three years it is estimated just 220,000 people in England will benefit, out of 3.4 million who are eligible.

Prof Sattar, from Glasgow University, says it is a simple matter of economics: “The cost of the drugs is still at a level where we cannot afford to treat several million people within the UK with these drugs. It would simply bankrupt the NHS.”

He estimates it costs the NHS about £3,000 a year to give a patient either Mounjaro or Wegovy.

So if everyone eligible in England received them right now, that would be about £10bn annually – half the entire NHS drugs budget.

Jean, who is 62, hopes Mounjaro will help her to get her weight and health back on track. She shows me a picture of herself on her phone from a decade before, when she was visibly far lighter and healthier.

“I was a fitness fanatic. I went to the gym practically every day. I don’t know what happened, why I fell off the wagon.”

She believes her relationship with food is “terrible”. “I have a lot of food noise and I tend to act on it,” she says, using a term coined to describe cravings and preoccupation with food.

Jean is eligible for Mounjaro because she has type 2 diabetes and has been injecting insulin for five years.

She is worried about side effects, which are similar to those for Wegovy, but will be carefully monitored at a diabetes clinic in south London linked to Guy’s.

Mounjaro helps stabilise blood-sugar levels and boost the body’s natural production of insulin.

After just five weeks on the drug, Jean is able to stop her insulin. She is delighted: “I think it’s Mounjaro, and willpower as well – I have to give myself some credit. I think the drug silences the food noise and I’m not constantly sitting around thinking about what I’m going to eat.”

After two months on the drug, Jean is back in the gym, and has lost more than 3kg (half a stone).

She is disappointed in her weight loss, but determined to shed more pounds as her Mounjaro dose is increased.

But Jean and the other patients getting Wegovy and Mounjaro on the NHS are the minority.

Prof Sattar reckons more than nine in 10 patients currently on weight-loss drugs in the UK are paying for them privately.

He points out that obesity rates are highest in areas of social deprivation.

“The people perhaps who stand to benefit the most, who are less affluent and from more deprived communities, are simply not able to afford this drug. It’s not fair. It’s just a reality of the economics of the situation.”

But Prof Sattar told me that rising obesity levels could also eventually “bankrupt” the NHS.

With smoking levels continuing to fall, he now regards excess weight and obesity as the “major driver, bar none, of long-term multiple health conditions”.

Both he and Prof McGowan believe that weight-loss jabs have an important role to play and could eventually bring some wider savings.

Prof McGowan says Ray is a good example: “We treat a lot of the complications associated with obesity. Ray has pre-diabetes. We’re hoping to go into remission and therefore prevent all the complications associated with that progressive disease.

“He might need joint surgery but achieving weight loss can prevent a lot of complications and ultimately save the NHS a lot of money.”

Prof Sattar says in 10 years there could be 20 weight-loss drugs on the market, including some in tablet form. As more effective and cheaper drugs become available, they could produce savings for the NHS, he says.

The UK government also thinks weight-loss drugs could eventually bring wider economic benefits.

A five-year trial in Manchester will look at the wider impact of Mounjaro beyond the individual health benefits, including whether it helps some people struggling with obesity to get back into work.

The drugs are not a magic bullet for obesity, but after decades of expanding waistlines, they offer hope to millions.

For now, though, the health service doesn’t have the resources to treat all those eligible. It means – for years to come – only a minority like Ray will get access on the NHS. The rest will have to pay – or go without.