Archaeologists Dr. Wim van Neer, Dr. Bea De Cupere, and Dr. Renée Friedman have published a study on the earliest evidence of horn modification in livestock in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

The researchers found the oldest physical evidence of livestock horn modification and the first evidence of such for sheep. Discovered at the elite burial complex in Hierakonpolis, Upper Egypt (ca. 3700 BC), six sheep showed evidence of deformation, adding to the history of horn modification in Africa, which has been primarily restricted to cattle.

“This is the earliest physical evidence for horn modification in livestock. The practice also existed in cattle but is, for that early period, only attested by depictions in rock art,” says Dr. van Neer.

Sheep were first introduced to Egypt from the Levant around the 6th millennium BC, becoming one of Egypt’s most important livestock resources by the 5th millennium BC. They were depicted on jars, carved reliefs and ritual vessels. It is from these depictions that it is known the earliest sheep in Egypt were of the corkscrew-horn variant.

These corkscrew-horned sheep were later adopted into hieroglyphics and became part of religious iconography in the form of ram deities with corkscrew horns. However, by the Middle Kingdom, the ammon sheep began appearing in Egypt. These sheep were characterized by crescent-shaped backward-pointing horns. Eventually, these ammon sheep completely replaced the corkscrew-horned variant.

At the site of Hierakonpolis, around 100km from modern Luxor, an elite burial complex was being excavated. Here, the city’s elite were buried in elaborate tombs together with wild and sometimes exotic animals, including cattle, goats, crocodiles, ostriches, leopards, baboons, wild cats, elephants, hartebeests, hippos, and aurochs.

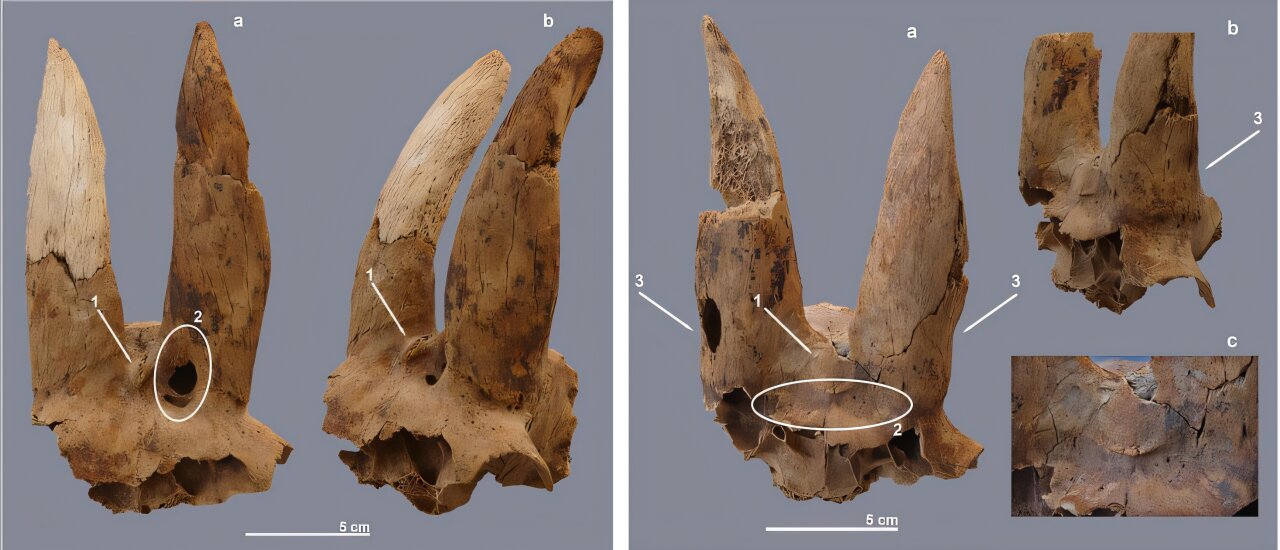

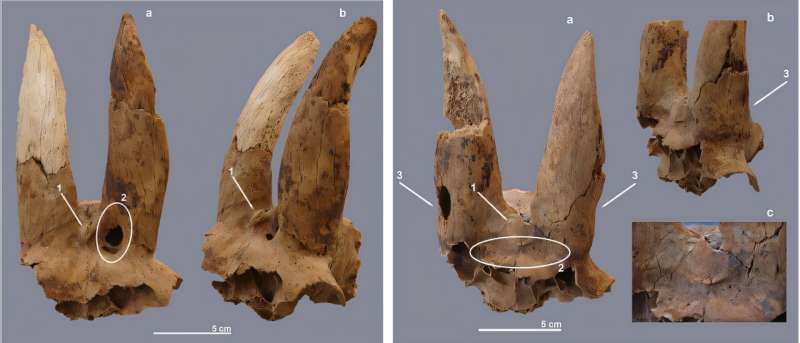

Among the animals they were interred with were also sheep. In tombs 54, 61, and 79, specifically, researchers discovered the skulls of six individuals whose horns had been modified. These included horns that were removed entirely or pointing backward or parallel and upwards to some degree.

Further examination of the remains also indicated that some of these sheep had been castrated, as indicated by the elongated appearance of their bones and the presence of unfused bones, making them larger than their uncastrated counterparts.

The modification of the horns was determined to have resulted from fracturing, a process in which the skull at the base of the horn core was fractured, repositioned, and tied together for a few weeks until the fractures healed.

This was determined based on the depressions found at the base of the horn cores and the unusually thin bone in this area (which are usually the result of fractures), as well as constrictions found on the sides of the horn cores, which were consistent with having been tied to hold the horns in place.

Various African agro-pastoralist groups, including the Pokot of Kenya, still use the same method of modifying horns today. They usually do this to their goats when they are around one year old.

When asked why the elite of Hierakonpolis would have wanted to modify the horns of their sheep, Dr. van Neer explained, “This is an indication that the rulers buried in the elite cemetery wanted to display their power not only by the keeping of wild and exotic animals (baboons, elephants, hippos, crocodiles, aurochs…) but also by modifying their domestic animals.

Discover the latest in science, tech, and space with over 100,000 subscribers who rely on Phys.org for daily insights.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates on breakthroughs,

innovations, and research that matter—daily or weekly.

“The sheep were castrated and thus larger than the average sheep bred for consumption. In addition, their shapes were modified by forcing the horns upward or by removing the horns. So, these were just two different ways of making ‘ordinary’ animals ‘special.”‘

By modifying the horns of the sheep, not only did they aesthetically look different, but perhaps could have symbolized the elite’s ability to control and manipulate nature itself. This concept was deeply important in Predynastic Egypt and is reflected in their procurement and burial of dangerous and wild animals such as elephants and baboons.

The researchers also suggest the modified sheep may have meant to evoke the addax (Addax nasomaculatus) with its upright spiral horns, which are often thought to symbolize the renewal of life and order over chaos.

What is certain is that these sheep were special and unlikely to have been bred for consumption, as evidenced by their castration and also their age (6–8 years), which would have been unusual, as most sheep bred for consumption are slaughtered by the age of 3.

The researchers will continue their excavations at Hierakonpolis, with Dr. van Neer noting, “We will keep our eyes open for other examples of horn modification at the site of Hierakonpolis; in particular, we want to know whether horn modification was also practiced in cattle and goats.”

More information:

Wim Van Neer et al, The earliest evidence for deformation of livestock horns: The case of Predynastic sheep from Hierakonpolis, Egypt, Journal of Archaeological Science (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2024.106104

© 2024 Science X Network

Citation:

Archaeological study uncovers world’s oldest evidence of livestock horn manipulation (2024, December 15)

retrieved 15 December 2024

from https://phys.org/news/2024-12-archaeological-uncovers-world-oldest-evidence.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.