Back in 2008, Jesse Eisenberg and his wife, Anna Strout, visited the former Nazi concentration camp Majdanek in eastern Poland. Because it is not far from the Russian border, he says, there was no time for the retreating Germans to clean up, so it is preserved very much as it was. Other death camps were reconstructed as museums, full of information. Majdanek is, he says, “like walking through a nightmare”. Eisenberg’s family lived in a small town just a few kilometres away. If the Holocaust hadn’t happened, he might be living there now.

More than a dozen years after that trip, Eisenberg was working on the script that would eventually become A Real Pain, his new film – one part memoir, one part whip-smart comedy, several parts emotional rollercoaster – in which he and Kieran Culkin play Jewish cousins who agree to spend their respective bequests from a revered great-aunt on a trip to Poland. They owe it to her to see the places their family had to leave behind when they fled to the United States, the only life they have known.

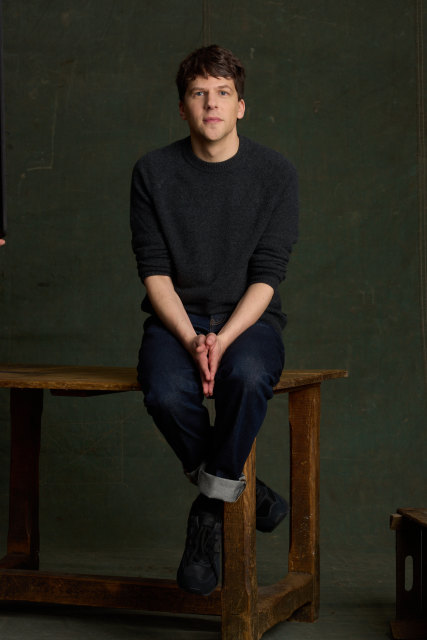

Jesse Eisenberg wrote, directed and stars in A Real Pain.Credit: Steve Schofield

Eisenberg wrote and the directed the film, and also plays David, one half of the daring duo. David is nervy, conventional, worried about keeping within the rules. Culkin plays Benji, his childhood playmate, who’s long since drifted into drugs, psychodrama and scrounging nights on other people’s couches. He is also, by turns, charming, obnoxious and very sweary. They are on a “Holocaust tour”. It is a random assortment of people, as these things are, but everyone has his or her own unhappy reason for being there. At the same time, they’re on holiday. Nobody knows what note to strike, least of all the Oxford scholar who, as their guide, keeps wanting to tell these grieving people interesting facts about gravestones.

My assumption was that A Real Pain was a long-cherished personal project, but Eisenberg originally set out to write about two friends travelling in Mongolia. “I’d done these tours through China and Tibet, Guatemala and Venezuela,” he says. For whatever reason, the dynamics of a group crossing the Gobi Desert didn’t feel like enough to sustain a film. “But as I was kind of banging my head against the computer, an ad banner popped up on the internet. The ad said ‘Auschwitz tours’ and then, in parentheses, ‘with lunch’. And I was like: that’s the movie. That’s the movie!”

Jesse Eisenberg on the set of A Real Pain. Credit: Suplied

He had first felt the winds of Auschwitz-with-lunch when he went to Majdanek, even though there was no catering involved. No matter how invested he was in that experience, he could never be more than an observer. “Because, on the one hand, you can’t force yourself into a similar situation to that of the people who suffered,” he says. “You can’t sleep outside the night before because you’re visiting a concentration camp; you have to go to a hotel. And maybe you have Marriott points, so you stay at the Marriott. Suddenly, you’re living your middle-class comfortable life, while exploring the trauma of your family’s history. I thought it would be interesting to explore that.”

Eisenberg, 41, grew up in a secular family of academics; his father had a PhD in social sciences. Young Jesse was burningly interested in NBA basketball; teenage Jesse was absorbed in the arts; nerdy Jesse, at whatever age, learnt to deflect bullies by being funny. He felt very American, while being peripherally but constantly conscious of his Jewishness. He was aware of having different holidays. “And I knew that certain people hate us, like the Ku Klux Klan. For a certain period of time, I was worried they were going to throw a flaming fireball through my window, so I would duck as I passed by it. Just a little kid’s paranoia, but that kind of stuff gives you what I would call an outsider experience, even if mostly it felt like an insider experience.”

James (Will Sharpe), the tour guide, is an outsider who wants in: he is an example of what Eisenberg calls philosemitism. “I noticed sometimes other people being interested in my family’s life and antisemitism. ‘Oh God, can you believe what happened in Brooklyn today, this kid got punched in the face!’ They want to commiserate with me, as if my interest is the same as theirs, and my interest is not the same. So yeah, philosemitism is an interesting thing. James, for me, is that kind of character, with this outsider’s interest in the Jewish experience that is almost fetishised.”

Jesse Eisenberg and Kieran Culkin play old friends.

He is no stranger to that urge himself. When he was younger, he became obsessively absorbed by the Serbian invasion of Bosnia, which had been a TV news constant when he was a child. “I don’t have family from Bosnia, I didn’t live through that war, and yet I found myself obsessed, visiting Bosnia and asking people about it.” It was, he sees now, as if he wanted to carve out his own corner of genocidal history. “There is something strange, something not pretty about that. I became interested in the war, I think, because it coincided with feelings I was having that I couldn’t place because my life was materially OK. So when I was older, I guess I saw the Bosnian war as kind of a version of my family’s history, but during my lifetime.”

‘I see myself as somebody in an industry that is totally uninterested in giving me jobs.’

Kieran Culkin isn’t Jewish. Eisenberg approached him to play Benji after sharing a scene from the movie with his sister, and she insisted that Culkin was the only actor who could do it. “We thought maybe we should cast a Jewish actor, but in the end what I came away with was Kieran giving this incredible gift to me and my family by being in this movie and by reflecting a story that maybe is very culturally specific to my life in a way that is most authentic. There couldn’t be a better actor for it. His urbane quality, his wit, his constantly staving off some kind of sadness: that all rings really true to me.”

Kieran Culkin (left) was cast as Benji on the recommendation of Jesse Eisenberg’s sister.Credit: Wiktor Szymanowicz/Future Publishing via Getty Images

Benji is feckless and annoying, but he is also the life of the party; people warm to him in a way that they don’t incline to buttoned-up David. There are years of smothered love, resentment and jealousy between them which bubble up as they confront their past. At these moments, the skin separating David from Jesse feels very thin. Playing characters very different from him, like the arrogant magician in the Now You See Me franchise, can be empowering; to play people who share his anxieties can be a great relief. “In this movie, I’m crying on the roof talking about how inadequate I feel around my cooler cousin. That’s stuff I feel all the time with other men, you know, feelings of inadequacy, but it would be really weird to start crying to a friend, ‘I’m feeling inadequate around you’ – that would be such a burdensome thing to do to another person. And yet it’s amazingly cathartic to get to do it in a movie.”

This is only Eisenberg’s second film as a director, but he is a prolific writer and director for theatre, and has written a slew of short stories for magazines including The New Yorker and McSweeney’s. He first made an impression as an actor in The Squid and the Whale (2005); he has since played roles as varied as Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network (2006), Lex Luthor in Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016), and a furry Bigfoot in the recent indie gem Sasquatch Sunset. On television, he led the hit miniseries Fleishman is in Trouble.

His first love was musicals; the next film he hopes to direct would also be a musical. Is he more of an actor, a writer or a director? “Oh, I see myself as somebody in an industry that is totally uninterested in giving me jobs, which is to say I’m in a very fickle, unstable industry that owes you nothing,” he says.

Jesse Eisenberg as Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network.

“You could one day be in something successful and beloved and the next day find yourself being given a [Golden] Raspberry Award and people on the internet writing about hating you. My first movie (When You Finish Saving the World, 2022), people didn’t like as much, so it sort of got discarded. Nobody I knew even saw it. This movie seems to be really well-liked, but I put the same effort into both of them. My next movie as a director is a musical. I’m desperate to get my music out there because I genuinely feel that if I don’t take advantage of every possible little skill set I have, I’ll just be out of work.”

A Real Pain was shot in Poland. It had to be, of course, but he also benefited from the wide and deep talent pool that is Polish cinema culture, fostered by the national film school that has such a high reputation that students willingly enrol for a year’s intensive course in Polish to study there. Local authorities did everything possible to help, including digging out information about the Eisenberg family history, on the basis of which he was able to gain Polish citizenship for himself, his wife and son. There is an enduring hostility to Polish people among American Jews, he says, which he believes is misguided.

Claire Danes and Jesse Eisenberg in Fleishman Is in Trouble.Credit: Linda Kallerus/FX

“I feel nothing but complete warmth to the Polish people I met and worked with and the people who ran the concentration camp who spent every day in this kind of thankless environment, working every day to preserve the memory of my family’s history,” he says. “I feel so indebted to them. If the war didn’t happen, we’d be here.” His own family went first to Galveston, Texas, but it could just as easily have been Melbourne.

Loading

“It’s just fascinating to me when I meet someone, say, in Australia and discover our families come from kilometres apart. If it weren’t for a fluke of history, we’d all still be together.” Which would make him, most likely, a very different person. “Yes. And if you’re feeling good about your life, you probably thank your lucky stars you ended up where you did. But if you’re looking for meaning in your life, you probably lament the fact that you’re so disconnected from your family’s history. And I’m both. I’m definitely both.”

A Real Pain opens in cinemas on Boxing Day.

To read more from Spectrum, visit our page here.