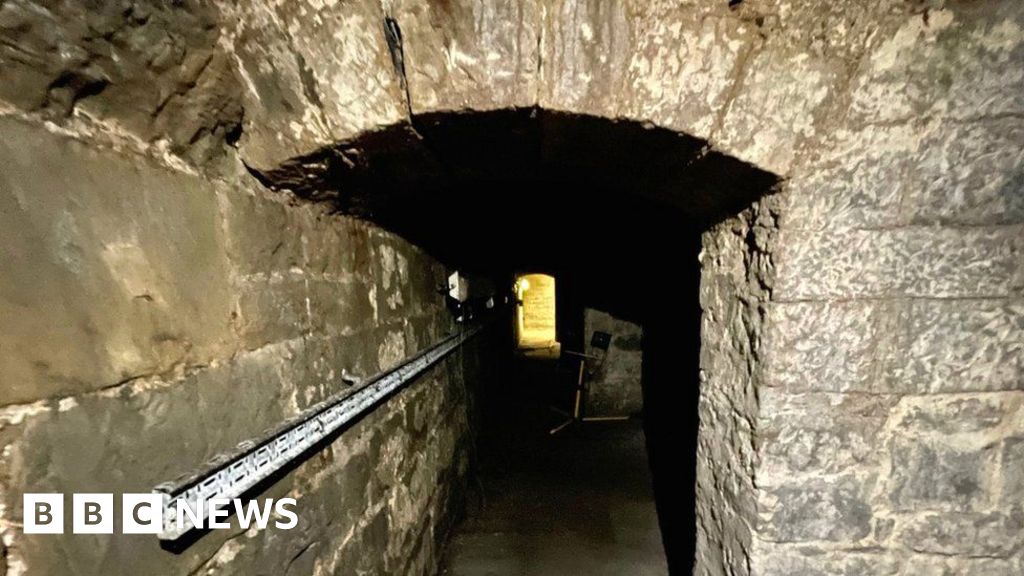

Behind a door deep within the lower floors of the National Library of Scotland lies a forgotten street which gives a glimpse of how Edinburgh looked centuries ago.

Libberton’s Wynd, in the heart of the old city, was demolished to make way for George IV Bridge in the 1830s – but part of the street still remains.

It can be found between the bridge walls and the library building, with access through a hidden door.

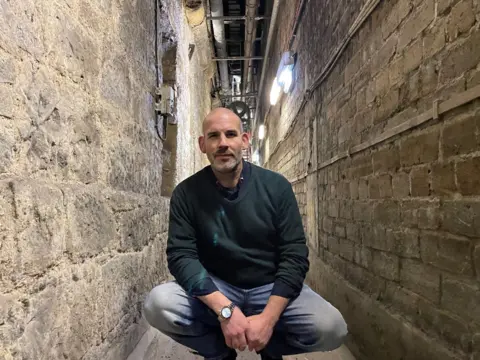

The corridor – which has been named The Void by library staff – is not open to the public, but BBC Scotland News has been allowed to see inside.

It was discovered by library officials in the 1990s when they broke down a small hatch on a wall behind filing cabinets, then crawled through it.

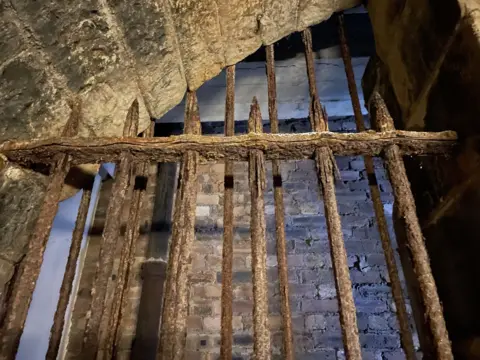

They found a passage with arches into chambers and rooms which are thought to have once been storage in the bridge.

Wikipedia

WikipediaBill Jackson, former director of the library, told BBC Scotland News he found old rotten furniture, ledgers, shoes and a slate urinal that were all more than 100 years old, but were waterlogged and damaged.

“My torch was hardly illuminating anything, it was very dark when I went through and a bit scary and I wanted to get out of there.

“It was fascinating though.”

Since then he has fitted lights and another door at the Cowgate end of The Void.

The library’s rooms were built on top of foundations, which can still be seen, of buildings that were demolished in Libberton’s Wynd to make way for George IV Bridge.

Robbie Mitchell, a reference assistant at the library, said that inside the passageway you could see the brickwork of the library’s lower levels and the bridge’s stonework.

“Although not a preserved street like Mary Stair’s Close, this nevertheless offers us a glimpse of the Edinburgh of centuries ago,” he said.

“There are several maps and accounts of the Old Town in the library’s collections which help us build an atmospheric picture of the neighbourhood on which both George IV Bridge and the library now stand, and what was there before The Void.”

George IV Bridge was built as a route to connect the centre of Edinburgh – the Royal Mile – over the Cowgate, which was in a valley, to the south side of the city.

Its arches had chambers built into them on several floors for storage for the shops at the top of the bridge.

Libberton’s Wynd was the route from the Cowgate to Edinburgh’s gallows in a section of the Royal Mile called The Lawnmarket – before it was demolished to make way for the bridge.

Later, The National Library of Scotland was built on top of the bridge, with floors running all the way down into the Cowgate below.

The bridge was built on Libberton Wynd’s foundations, which can still be seen in The Void.

The corridor runs for several hundred feet at a steep gradient.

Officials have widened the entrance so there is now a full-sized door. Some of the chambers are now used to store huge water tanks for the library’s sprinkler system.

Mr Mitchell said that large crowds, often several thousands strong, attended the executions which took place at the city gallows where Libberton’s Wynd joined the Lawnmarket.

One of the most infamous figures to have been executed there was body-snatcher and murderer William Burke in January 1829.

Libberton’s Wynd was also famed for housing one of the city’s best-known taverns, which was called The Mermaid before it became Johnnie Dowie’s Tavern.

Taverns were key features of Edinburgh’s Old Town communities, and patrons often came from various social classes.

John Dowie was described in accounts as “the sleekest and kindest of landlords”. He always wore “a cocked hat, buckles at the knees and shoes, as well as a cross-handled cane, over which he stooped in his gait”.

City of Edinburgh Council – Capital Collections

City of Edinburgh Council – Capital CollectionsMr Mitchell said the most popular drink had been the Edinburgh Ale brewed and supplied by Archibald Younger.

This was described as “a potent fluid which almost glued the lips of the drinker together, and of which few, therefore, could dispatch more than a bottle”.

Mr Mitchell said descriptions of the tavern, which occupied the ground floor of a tall tenement, gave an impression of the claustrophobic confines of the Old Town.

About 14 people could fit in its principal room, which looked to the Wynd, but the other rooms were said to be so small that no more than six people could fit in each of them.

They were described as being “so dingy and dark that, even in broad day, they had to be lighted up by artificial means”.

City of Edinburgh Council – Capital Collections

City of Edinburgh Council – Capital CollectionsThe Tavern was described as a house of “much respectability” and was a popular meeting place for “the chief wits and men of letters” in Edinburgh.

It was regularly frequented by writers including poet Robert Fergusson, artists and many members of the judiciary.

The smallest of its windowless chambers was an irregular oblong box which was commonly referred to as “the Coffin”, and was believed to be Robert Burns’ favoured seat in the Tavern.

Libberton’s Wynd was first referred to in the late 15th Century, but had been demolished by 1835.

Local historian Jamie Corstorphine said entering The Void had been one of the most exciting things he had experienced.

“The name of the wynd probably came from Henry Libberton, who had a large property on the wynd – or if not him, then his family, who remained in the house for many years after his death in 1501.

“The street had merchants, barbers, a shoemaker, grocers, custom house, vinters, cork-cutters, silver turners, hosiers and glaziers.

“It was a very busy street that would have been full of life at the time.”