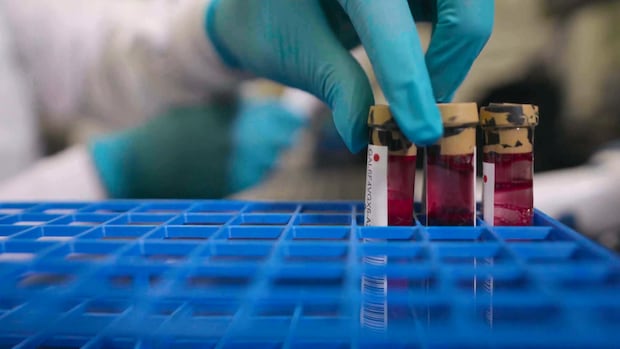

It’s an idea that thrills cancer researchers: a blood test that has the potential to screen for a sweeping number of cancers before symptoms appear.

That’s the premise behind Galleri, a test that looks for traces of the DNA that cancer cells shed into the bloodstream.

“The Galleri test screens for many of the deadliest cancers before they become symptomatic, including those without recommended screening tests,” says Grail, Inc., the California-based health-technology company that created the test.

Until now, it has only been commercially available in the U.S., where more than 250,000 have been sold. Galleri is now available in Canada through Wellness Haus, a private clinic in Toronto, at a price of $2,099 per test.

Dr. Melissa Hershberg, medical director of Wellness Haus, says about 50 patients have taken the test in the three months since her clinic started offering it.

“The Galleri test has been on my radar for years because I’ve had several patients go to the U.S. to get it done there,” Hershberg told CBC in an interview.

Galleri is one of an emerging class of screening methods known as multi-cancer early-detection tests, or MCEDs. The idea is to screen for dozens of cancer types at once in the hopes of catching it at its early stages, when it’s generally easiest to treat.

In the U.S., the National Cancer Institute is poised to launch the Vanguard Study next year into the feasibility of MCEDs as a screening tool. The study begins with 24,000 people, with the ultimate aim of determining whether the tests can reduce deaths from cancer.

The U.K.’s National Health Service (NHS) has recruited 140,000 participants in what it describes as the world’s largest trial of an MCED, trying to find out if screening with Galleri reduces the likelihood of a late-stage cancer diagnosis.

“The test is still in its infancy,” Hershberg said, adding that researchers are “still doing studies on it. So it’s not something that I go and tell everybody to go do.”

The enthusiasm about Galleri’s potential is tempered by questions about its effectiveness as a broad-based screening method for the population.

A private clinic in Toronto is the first in Canada to offer a new cancer screening blood test called Galleri, but questions remain about the effectiveness of the $2,100 test.

Dr. Eddy Lang, who teaches at the University of Calgary medical school, is wary of the hype.

“The problem as I see it is that the test has not yet been proven to improve patient outcomes,” said Lang in an interview. “Until we have studies that show that people actually live longer as a result of getting the test, I think we need to be very apprehensive about using it.”

Grail recommends Galleri annually for people age 50 and up, or anyone with an elevated risk of cancer related to obesity, diabetes or smoking. The test has not been cleared or approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and Health Canada said in a statement that it doesn’t regulate lab-developed tests.

Test doesn’t diagnose cancer type

Galleri clinical trials — funded by Grail and published in peer-reviewed medical journals — have shown that the test finds a cancer DNA signal in roughly one per cent to 1.5 per cent of people in the recommended age group.

However, a positive Galleri result doesn’t specify what type of cancer someone might have. That requires further scans and procedures.

False positives are also an issue. The results of a clinical trial led by Grail scientists, published in the Lancet journal in 2023, showed that follow-up tests were unable to find any cancers in 62 per cent of people who had such a signal detected on the Galleri test.

Lang is also a member of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, an independent advisory body that reviews evidence on the effectiveness of population screening in those without symptoms.

He is concerned that false positives on the Galleri test could send people into the public system for unnecessary scans, treatments and even surgeries, along with the anxiety that comes from such a result.

“I think a healthy consumer skepticism is the way to go,” said Lang.

A study published in 2020 evaluated Galleri’s sensitivity: how well it performed at catching the DNA signal in people who had already been diagnosed with cancer. Of the 2,482 patients tested, Galleri detected just 18 per cent of cancers that were at Stage 1 and 43 per cent at Stage 2, while detection rates were noticeably higher at Stage 3 (81 per cent) and Stage 4 (93 per cent).

NHS data ‘not compelling enough’

At the launch of its clinical trial, the NHS initially hailed Galleri as “potentially revolutionary” and said it would expand the screening to one million people if the preliminary results were satisfactory.

The results didn’t meet that bar.

The NHS announced in May that its “did not find [the preliminary data] compelling enough to justify proceeding straight away with a large-scale pilot programme of the test in NHS clinical practice.”

Instead, it will wait for the trial’s final results in 2026, and then decide whether the test has a role in the U.K.’s publicly funded medical system.

Dr. Clare Turnbull is an expert in cancer genetics at the Institute of Cancer Research in London, and is not directly involved in the NHS trial. She says the preliminary results — which have not been published — must have failed to persuade the health-care system to invest further money and resources into wide-scale use of Galleri for now.

“The technology is absolutely incredible,” said Turnbull in an interview. “It’s just seemingly from the data thus far, it is not good enough, it is not sensitive enough around early-stage cancers.”

Turnbull says she also worries a negative result on a Galleri test may provide people with what she calls “false reassurance” that they are cancer-free.

“People think that since they have had a blood test, they don’t need to participate in other screening, like mammography or bowel screening, and potentially they ignore symptoms.”

‘Holy Grail’ of cancer screening

Grail’s co-founders gave the company its name because they believed such a blood test could be the Holy Grail of cancer screening.

Despite that ambition, the company says the test does not replace any existing routine cancer screening recommended by a doctor, such as a mammogram for breast cancer, a pap smear for cervical cancer, or a fecal immunochemical test for colorectal cancer, also known as the FIT or at-home poo test.

Dr. Keith Stewart, director of the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, believes there will be a role for Galleri and tests like it in future screening, but more likely for people at high risk of cancer rather than the population as a whole.

“This is amazing technology,” Stewart said in an interview.

“The question is, is it cost-effective? How often do you get an accurate result? How many times does it pick up a very early cancer versus a late cancer? Those are still things in the research domain for the large part.”

Affordable for a public system?

Princess Margaret is one of the participating hospitals in Pathfinder 2, a clinical trial of Galleri, to be completed in 2026. The Grail-sponsored study of 35,000 patients aged 50 and up aims to assess how many procedures are required to find a diagnosis after a cancer signal is detected by a Galleri test.

Stewart says that study should reveal the costs of doing wide-scale screening of the population to find the small proportion that have an early-stage cancer.

“Is that something that’s affordable for a public health system? I think the answer today is no,” Stewart said. “I think in completely healthy people, it may be hard to justify that kind of expense.”

While the makers of Galleri say that it screens for more than 50 types of cancer, the data so far seem to suggest that its screening potential is greater for certain types of cancer than others.

For instance, that 2020 study showing it detected just 18 per cent of all Stage 1 cancers also showed that it detected 39 per cent of Stage 1 cancers from a pre-selected list of a dozen types, including pancreatic and uterine cancer.

“The reality is there’s not going to be a single test which is useful to detect all cancer types,” said Turnbull.

The commercial reality is that having Galleri adopted as a wide-scale screening method could be a financial bonanza for Grail and its shareholders.

To get a sense of the money at stake: U.S. biotech giant Illumina paid $7.1 billion US to take over Grail in 2021.

Illumina was subsequently forced by European and U.S. regulators to divest the bulk of its holdings in Grail this past summer, over antitrust violations. Grail’s market cap is now at just $590 million US.

Jonathan Kolber, a Toronto executive in his mid-50s, said he “signed up immediately” when Galleri became available at Wellness Haus.

“If someone can be ahead of preventing a Stage 1, 2 or 3 cancer, it’s certainly worth every penny,” Kolber said in an interview.

No cancer signal was detected in his test.

“It does give you peace of mind, if the test is accurate, that you are clear for the moment.”

Tests like Galleri not regulated by Canadian health authorities

In a statement, Health Canada said it does not regulate laboratory-developed tests such as Galleri, and said that responsibility rests with the provinces.

Ontario’s Ministry of Health said it does not regulate elective tests that people choose to pay for.

“There is no data to support [Galleri’s] use for population-based testing,” said a Ministry of Health official in an email to CBC News. “As with any unregulated and unapproved test, patients are advised to proceed with caution and to seek advice from their health-care provider.”

Grail “does not promote the use of the Galleri test by individuals in Canada,” said company spokesperson Kristen Davis in an email to CBC News.

“The Galleri test is prescription-only and requires an order by a provider with prescribing authority under applicable U.S. law.”

Hershberg complies with this requirement by partnering with an eligible health-care provider in the U.S. when she consults with each patient about the test and the result.