ESSAYS

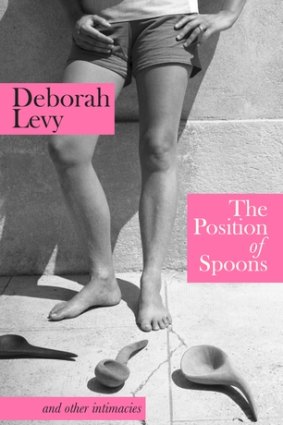

The Position of Spoons and other intimacies

Deborah Levy

Hamish Hamilton, $45

The diminished space criticism enjoys comes as no surprise. Freelance writing outliving the time and context of its creation? Out of touch. Published collections of what might (generously) be called hack work are rare. Who do you think you are, composing a piece of writing-on-the-fly, thinking it might – if the heavens align and the tarot cards land right – live on, worthy of appreciation years, if not decades, after its commission?

Maybe you’re just one of the faithful. A quixotic clown or conjurer. Or maybe you’re Deborah Levy.

Levy’s new book is a joyful anachronism. A sense of possibility. Slugs, snails and puppy dogs’ tails. We have anecdotes, fictional filigrees, homages to fabulists (Lewis Carroll, Baudelaire, Kenneth Anger), to Blade Runner and artist Francis Upritchard; poems and appreciations (Paula Rego! Meret Oppenheim! Lee Miller!); prayers for the dead (Hope Mirrlees, early modernist writer and intellectual flaneuse; Francesca Woodman, known for her kinetic chiaroscuro portraits). Writing, Levy observes, is mostly a way of looking.

Her introductions to authors are thus intensely personal. It is not the critically distant or anonymous voice of the scaredy-cat journalist or too-cool academic. It is not the voice that fears or perhaps mistakes intimacy for presumption, avidity for naivety. It is in communion with its subjects.

Until the turn of the century it was not unusual to see critics collect their odds and ends into anthologies. I think it is part of the joy and solace of criticism to think that it is still possible. When Levy describes French author Colette as “glamorous, serious, intellectual, playful”, she’s envisaging Colette as proto-punk, whirlwind DIY-er. “She was a working writer who had a purpose in life.”

Deborah Levy’s latest collection of essays has a joyful sense of possibility.Credit: Getty Images

For Levy, as a fellow practitioner, literary introductions provide an opportunity to reminisce, to speculate. To share in “Honey, I know” fellow feeling. Gallows camaraderie. Levy just gets what English literary experimenter Ann Quin felt of her artistic calling. Quin had – “just like my own clever, book-loving mother” – worked for a stint as a shorthand typist. As though the writers we treasure might be neighbours or family members. In a way, if our relationships with them become intimate enough, they are spiritual ancestors. Kinfolk to our innermost beings and desires. The collection’s very first line: “I fell in love with her [Colette] before I read any of her books.” Before Levy the critic had knowledge, she believed. Before experience, perception.

This is faith. Or desire. It is a large part of what Levy values in art. Because desire – like other intimacies – is a way of connecting to something you need to survive, if not to go on surviving.