White Coat Black Art26:30Virtual doctors for real ERs

Dr. Michael Ertel starts his emergency department shift at about 8 p.m., after making himself a cup of coffee and saying goodnight to his golden retriever, Norman. But he’s not going to the hospital.

“Time to head down into the bunker,” he said.

The “bunker” is the basement of his home in Kelowna, B.C., where he fills in for an emergency department he’s never set foot in. It’s hundreds of kilometres away in Mackenzie, B.C., a small community of about 3,300 people.

“Sometimes if we can’t do it, they shut down overnight,” Ertel told Dr. Brian Goldman, host of CBC’s White Coat, Black Art, during a Wednesday night shift in late 2024.

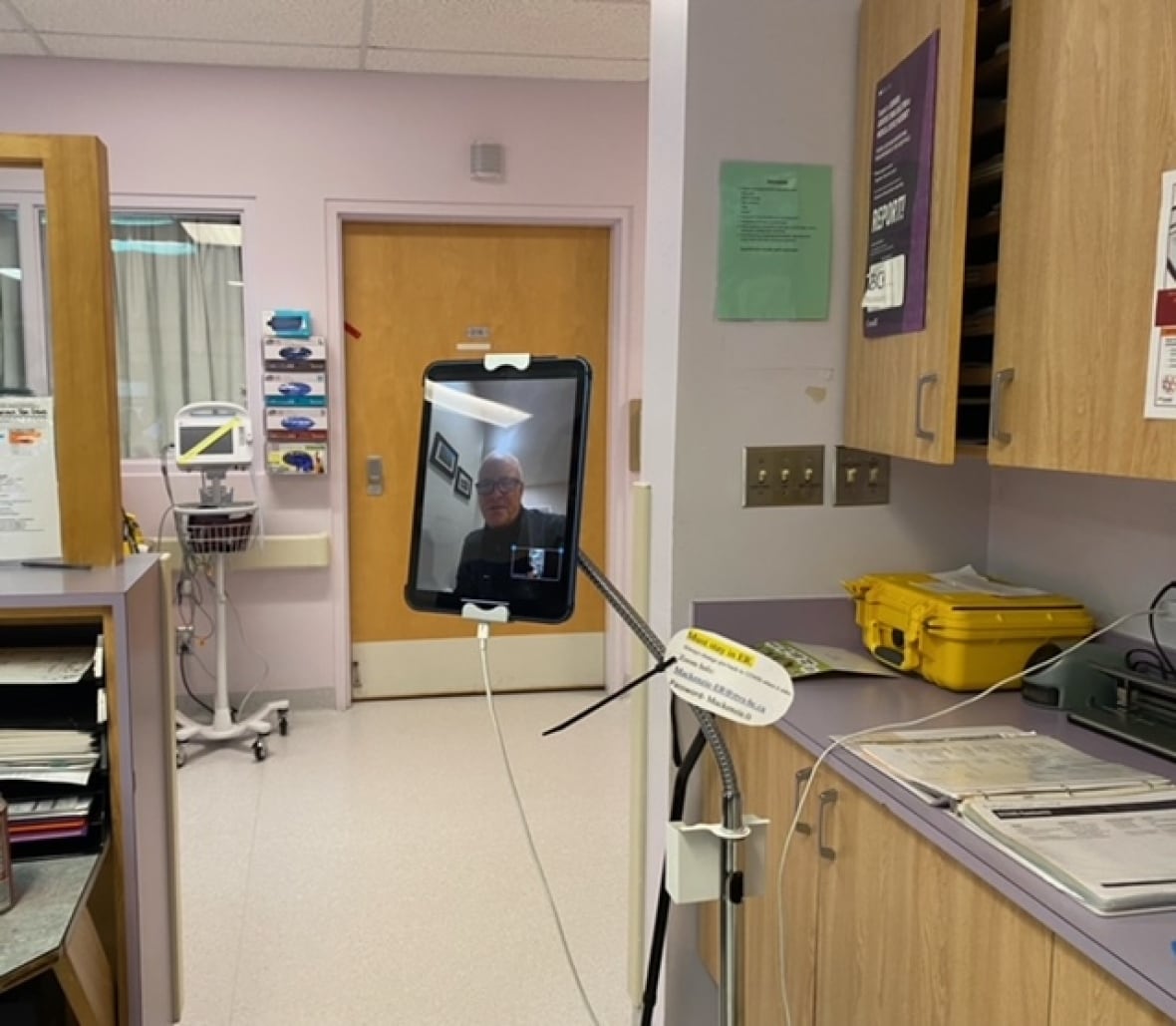

Ertel works virtually through a program called Virtual Emergency Room Rural assistance (VERRa), which deploys emergency physicians to work overnight shifts virtually for smaller emergency departments in B.C.

This virtual physician coverage is an attempt to keep rural ERs open for patients while health authorities in B.C. and across the country are trying to find and keep staff working in rural or remote areas.

In some communities, emergency centres close for hours or days when there isn’t enough staff.

Health authorities in several provinces are increasingly turning to virtual emergency care — in this case, when a physician is virtual and works with nurses on the ground to see patients over a video call as needed.

As Shaina Luck reports, the hope is that the technology can move patients through emergency departments more efficiently.

In addition to B.C., Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and Saskatchewan are also relying on similar virtual emergency care models. In Newfoundland, the virtual physician coverage is done by a private company, Teladoc Health.

Ertel sees value in the virtual coverage for both patients and local physicians but ultimately would prefer to see staff on the ground instead.

“Until that happens, we’ll do our best to help out,” said Ertel, an emergency physician who also works in-person at Kelowna General Hospital.

Some, however, aren’t completely sold on virtual emergency coverage. There are concerns around the quality of patient care and the costs of virtual care when a private provider is working in the public healthcare system.

Physicians also say it has to be used with in-person care.

“It would surprise me if it was really able to provide high quality care for the things that people might be coming into the emergency room for because the physician isn’t seeing the patient. It’s all virtual,” Fiona Clement, an associate professor and director of the University of Calgary’s Health Technology Assessment Unit, said in an interview about Teladoc Health in April.

How does an ER with virtual doctor work?

It’s a busy night at the Mackenzie and District Hospital and Health Centre’s emergency department during Ertel’s shift in late 2024.

Shak Karimi, a travel nurse, tells Ertel they’re over capacity and there aren’t enough nurses. The hospital goes on diversion, meaning patients transported by ambulance would have been sent to the closest hospital almost 200 kilometres away in Prince George.

“We’ll get through it. We always do,” Ertel, through video call, tells Karimi and the two other nurses working in Mackenzie.

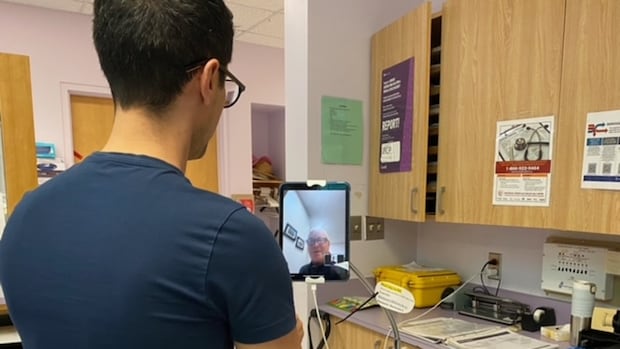

Most patients wouldn’t know that the doctor working in Mackenzie is hundreds of kilometres away. Like most emergency departments in Canada, the nurses on the ground are still triaging people.

Nurses like Amber Pasichnyk, who works in Mackenzie. She gathers as much information as possible from a patient before speaking to the virtual doctor. And, if needed, she connects the two.

“Without a nurse that’s able to do a skilled assessment and all those things, that system would not work at all,” Pasichnyk said.

She thinks overnight virtual emergency care is valuable for non-urgent cases, even if it can add to her already busy workload.

“If I have a bunch of patients waiting to be seen and I’m using [VERRa], sometimes it just takes a little bit longer for nursing to get through the patient load just because we’re having to stay with the iPad or move it around,” she said.

At the other end of the country, it’s a similar setup. It was a nurse who connected Wendy Martin, 62, to a virtual physician when she went to Twin Oaks Memorial Hospital in Musquodoboit Harbour, N.S. in April.

Martin thought she was experiencing symptoms of a heart attack. When she got to the hospital, the nurse triaged her and brought her to an exam room.

She waited about 15 minutes to connect with the doctor in Toronto. She was diagnosed with walking pneumonia despite no one checking her lungs, she says.

“I was a little hesitant to accept the diagnosis, more so than I would have been had the physician been right there with me.”

Martin would prefer to be diagnosed in person but says there is value in being able to access a doctor.

“At least you’ve spoken to a physician, [and] you can get your questions answered. So I think it’s better than nothing,” she said.

Can virtual ERs help with hiring and retention?

Back in Mackenzie, Dr. Lindsey Dobson is the local doctor on call during Ertel’s shift. A local doctor has to be available in case an urgent situation happens.

She has already worked a shift at the ER that day, and will see patients the next day at the local clinic.

She’s happy Ertel and physicians like him are available. This virtual coverage means she can spend time with her husband and children, and sleep.

“We have a huge number of diversions and not a lot of physicians covering our 24-hour care. So it means a lot and it’s a huge relief,” she said.

Ertel says that’s the benefit of virtual physician coverage: it gives local doctors time to rest and keeps the ER doors open.

The virtual coverage through VERRa and a previous iteration of the program has prevented over 5,000 hours of emergency department closure or diversion across B.C. since it launched in 2021, according to program officials.

The program, run by the Rural Coordination Centre of BC (RCCBC), is funded by the province’s health ministry and the Joint Standing Committee on Rural Issues. CBC News requested comment from B.C.’s health ministry but didn’t receive a response before deadline.

In Saskatchewan, the health authority there has said its virtual physician coverage is a “temporary measure” while it hires staff.

But doctors with the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP) say there could be benefits to having virtual care long-term.

“In the short term, we may address service gaps. But in the medium-long term, that partnership with the local community will extend recruitment, retention and the joy of practice in the rural emergency environment,” said Dr. Kendall Ho, an emergency physician and chair of CAEP’s digital emergency medicine committee.

But even with virtual doctors, many communities across Canada continue to deal with temporary ER closures, with those working in healthcare saying persistent ER closures are a symptom of larger healthcare issues. Virtual physician coverage in smaller ERs is just one of several potential remedies.

Ertel says other ideas like hiring more internationally-trained doctors and increasing enrolment in medical schools will also help, but it’ll take time.

“Until we get there, I think this is what we have to provide in the interim,” he said.