The federal government is asking Parliament to approve hundreds of millions of dollars in new spending to cover the health-care costs of eligible refugees and asylum seekers — a budget line item that has soared in recent years as the number of these newcomers reached record highs.

The Interim Federal Health Program (IFHP) is designed to cover migrants who don’t yet qualify for provincial or territorial medicare. By removing some barriers to health care, the program makes it easier for refugees — many of them fleeing conflict or persecution abroad — to get the care they need on arrival.

There’s also a public health benefit: it helps prevent and control the spread of infectious diseases in Canada.

Some resettled refugees receive health care through the IFHP for only a few months before transitioning to provincial plans. Some remain on the federal plan for much longer as they wait for their claims to be adjudicated — a process that now takes more than two years as Ottawa grapples with a mounting backlog.

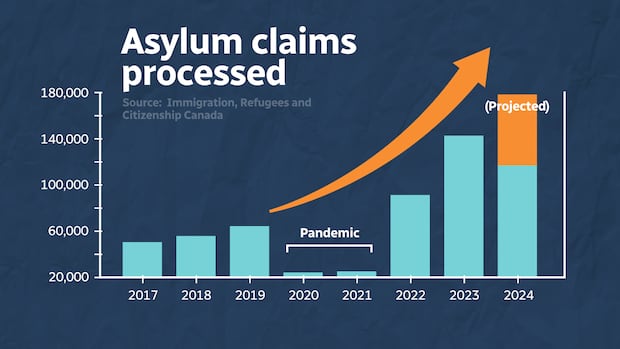

The IFHP’s cost has soared from roughly $60 million in 2016 to a projected $411.2 million this year, easily outpacing inflation.

The number of asylum claims around the world is growing, but an increasing share of them are now being made in Canada. Andrew Chang explains how Canada became the fifth-largest recipient of asylum seekers, and the public policy decisions that analysts say have contributed.

Former prime minister Stephen Harper’s Conservative government curtailed the IFHP and eliminated coverage entirely for some refugees and asylum seekers as part of a push to reduce spending and balance the budget.

The Harper government also said it was unfair for taxpayers to be paying for a program that was, in some instances, much more generous than what’s available to some Canadian citizens and permanent residents through public health care.

The decision to cut the program prompted a wave of criticism and was ultimately deemed unconstitutional by a Federal Court judge.

In 2016, the Liberals restored the program — which covers primary care, hospital visits, lab tests, ambulance services, vision and dental care, home care and long-term care, psychologists, counselling, devices like hearing aids and oxygen equipment, and prescription drugs, among other things.

A CBC News review of the data shows how much more the program is costing after years of global upheaval and the resulting influx of people fleeing to Canada.

A sevenfold increase in refugee health costs

When the Liberals announced the program’s restoration, the then-immigration minister said the program would cost roughly $60 million a year.

The cost quickly doubled to $125.1 million a year in 2019-20 and then more than doubled again to $327.7 million in 2021-22, according to government data.

In the government’s supplementary estimates tabled this week — part of the legislative process for asking Parliament for more money to cover initiatives that haven’t already been funded — Ottawa is now asking for $411.2 million a year for IFHP.

Donald Trump’s promise to crack down on illegal immigration in the U.S. is raising concerns about an influx of migrants crossing into Canada. Officials say the country simply can’t house them, while advocates fear migrants will risk their lives in freezing conditions.

A spokesperson for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) said the new funding for IFHP is to “cover costs related to health-care benefits for eligible beneficiaries as Canada continues to respond to elevated asylum claim volumes.”

“These funds will allow for continued delivery of the IFHP while offsetting costs on provinces and territories, and support the government’s commitment to facilitate care for some of Canada’s most vulnerable populations.”

A spokesperson for Immigration Minister Marc Miller did not address a question about curbing the number of asylum seekers to bring down the associated health-care costs.

The IFHP boost is just one of the budget requests in this year’s supplementary estimates. In total, the government is looking for about $1 billion more for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada this fiscal year.

Record-breaking number of asylum seekers, refugees

When the health program was fully restored in 2016, there were about 130,340 refugees and asylum seekers eligible for coverage, according to government statistics.

That figure doubled to 280,322 in 2019-20 as the federal government accepted many more new arrivals — many of them from sites like Quebec’s Roxham Road, where thousands of people have crossed into Canada “irregularly.”

As then-president Donald Trump clamped down on immigration and stepped up deportations, many more people decided to head north to avoid Trump’s dragnet. Canada also eased visitor visa requirements, which led to more asylum claims at airports.

While Canada and the U.S. have since moved to close Roxham Road and do away with “irregular crossings,” and as Ottawa again tightened visa restrictions, the flow of people claiming asylum and refuge in this country has not abated.

In the first nine months of 2024 alone, 132,525 people have claimed asylum — nearly as many as in all of 2023, which was already a record-seeking year.

About 53,000 refugee claims have also been filed as of September 2024 — a figure that’s higher than all of the claims filed last year.

A spike in new asylum and refugee claimants, combined with those who are already here, means the IFHP is on pace to cover more people and their health-care costs than it ever has before.

In a statement issued to CBC News, Tom Kmiec, the Conservative Party’s immigration critic, said Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and “his incompetent ministers broke our immigration system and allowed fraud, chaos and disorder to run rampant.”

“He encouraged irregular border crossings and invited asylum seekers to come to Canada. They did nothing about Roxham Road for more than six years and relaxed visitor visa requirements, resulting in a sharp hike in asylum claims at our airports. Now Canadians are paying the price for the chaos he created,” Kmiec said.

The Conservatives have said they will curb the number of new immigrants if elected by tying arrivals to housing starts. Kmiec did not say what the Conservatives’ policy on asylum seekers and refugees would be if they form the next government.

An asylum seeker — also called an asylum claimant or refugee claimant — comes to Canada seeking refuge and asks the government to consider them a refugee. These claimants typically spend months or years on the IFHP as they wait for Ottawa to review their files.

Resettled refugees, however, are in a different category, as they are referred to Canada by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, another designated referral organization or a private sponsorship group. They are screened abroad before being issued a visa to come to Canada.

These refugees usually transition relatively quickly to provincial health-care plans because they are considered permanent residents on arrival — but they do maintain some supplementary benefits like pharmacare for longer than other immigrants.

Past cuts to refugee health care were ‘disastrous’: expert

Y.Y. Chen is an associate professor at the University of Ottawa’s faculty of law and expert on the intersection of international migration and health.

Chen said the IFHP serves two purposes: one humanitarian, the other fiscal.

The program gives care to people who are often fleeing traumatic circumstances and have unique physical and mental health needs.

It’s also more cost-efficient to deal with health issues right away instead of letting them fester, Chen said.

“These refugees are going to be a member of our society in the long run. It’s to help them resettle in this society and get them integrated so they can start out on the right foot,” Chen said in an interview with CBC News.

“We also don’t want to leave any gaps when it comes to the prevention and control of infectious diseases,” he added. “It could undermine the health of society as a whole.”

Past Conservative cuts were “detrimental” and had a “disastrous effect on the health of refugees and refugee claimants,” Chen said, adding it would be very disruptive to curb these benefits in the future.

But Chen said the historic recent surge in new migrants is putting “a lot of pressure” on a health-care system that is already grappling with a shortage of family doctors and long wait times.

“Adding more people into the system will stretch it even thinner. That is a concern,” he said.