The Granddaughter’s other story is Kaspar’s. After a domestic tragedy leads him to seek out the truth about his wife Birgit’s past, he embarks on a quest to track down the daughter she’d abandoned before they met. He learns that, for Birgit – “a child of East Germany” – life has been about flight, and that it’s weighed her down.

For him, though, it’s about a search, one that takes him from the home they had shared in modern-day Berlin to Litzow and Lohmen in rural Germany. It’s there, about halfway into the novel, that he meets Sigrun, the granddaughter of the title, and comes face-to-face with the neo-Nazi movement’s “mountain of prejudice” – and a profound personal challenge.

The Berlin Wall under construction in 1961. Credit: AP

A former lawyer and university professor, Schlink writes clearly, concisely and occasionally colourfully. Attentive to the incidental details that bring his characters to life, he takes us inside their encounters with their surroundings: the joy of an exquisite sunset, the beauty of Brahms’ Symphony No. 4, the intimate pleasure of kneading dough, the enticing smell as it bakes.

But alongside the sensory immediacy of these experiences, he establishes an illuminating framework for their lives. Excavating the routines that, for better or worse, rule his characters’ everyday existence, he scrutinises the impact their country’s reunification has had on them, the values they’ve come to hold, and their fears that they might be doing the wrong thing.

While Germany’s history, its current crises and the novel’s geographical settings are presented as a background to their daily activities, they also serve as a formative influence on all the characters, shaping the contrasting ways in which they think about their relationships with each other and the world.

What binds them together is the troubled humanity they share and the changes that are as inevitable for each of them as the next breath they take. Some are able to adapt to the new circumstances they find themselves facing; others aren’t. Some can correct the mistakes they’ve made; others can’t.

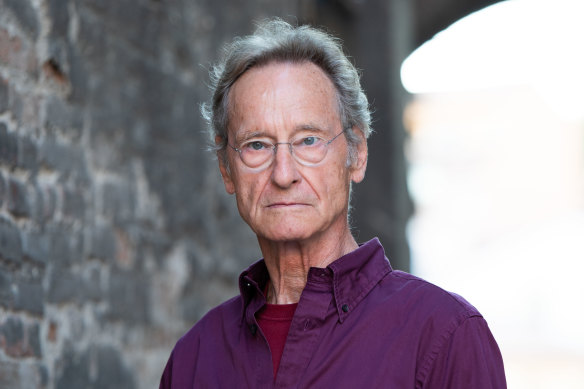

There are times when Kaspar seems indistinguishable from his creator, Bernard Schlink.Credit: Leonardo Cendamo

Driving the novel is the potent humanist impulse that has been evident throughout Schlink’s career, urging empathy for its central characters. It’s at its evocative and endearing best when Kaspar and Sigrun are sharing the page, their interactions fuelled by a heartfelt appreciation of the experience of grandfathering and embodying a positive life force. And it even offers a reminder that neo-Nazis and their like are only simplistically reduced to the horrendous beliefs they hold.

Schlink’s prose is direct and reflective. And, although he writes in the third person, there are times when he and Kaspar seem indistinguishable, the character alert to the themes running through his creator’s mind. “He would have liked to have had children,” Schlink writes of Kaspar. “Now he had a granddaughter. And now that he had her, he had to tend to her soul. He laughed. Sigrun’s soul, the German soul … What am I letting myself in for?”

Loading

Like Schlink in his estimable work as a writer, Kaspar’s journey into the past finds him grappling with the issues it raises for the present. Challenged about his beliefs, he again seems to be speaking for the author of his story: “I love my country. I’m glad that I speak its language, that I understand its people, that it’s familiar to me. I don’t have to be proud that I’m German; it’s enough for me that I’m glad of it.”

At its anguished heart, The Granddaughter is a state-of-the-nation story, one which, intriguingly, takes us from Berlin to Brisbane and eventually finds its way through a moral labyrinth to at least a qualified hope.

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.