Getty Images

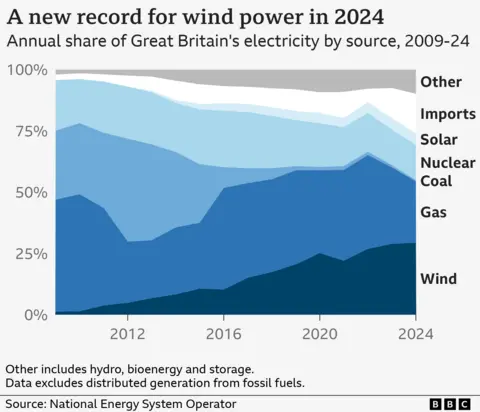

Getty ImagesWind provided more electricity than ever last year as the UK moved further away from planet-warming fossil fuels to power the nation, new data shows.

Wind generated nearly 83 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity across Great Britain (England, Wales and Scotland), up from nearly 79TWh in 2023, show figures from the National Energy System Operator (Neso), which coordinates electricity distribution.

Electricity generation from major fossil fuel power stations fell to just over a quarter of the total last year as other renewable sources, such as solar, also rose, along with electricity imports.

The government wants less than 5% of electricity to come from polluting fossil fuels by 2030.

Neso – the government’s independent system planner and operator for the energy transition – has previously described the government’s ‘Clean Power 2030 Action Plan’ as “achievable” but “at the limit of what is feasible”.

The government considers clean electricity to include renewables, such as wind, solar, hydropower and bioenergy, as well as nuclear power.

Together, these sources generated around 56% of Great Britain’s electricity in 2024 – a new high, according to preliminary Neso data that will be confirmed this week.

Major fossil fuel generation (mainly gas) fell to 26%, while a further 16% came from imported electricity.

Neso data does not cover Northern Ireland, which has its own electricity transmission system operator, SONI.

The figures only include fossil fuel and biomass generation from major power stations connected to the main transmission network. For these sources, Neso does not include smaller-scale operators that feed in electricity at a local level, although typically these contribute a relatively small fraction of fossil fuel power.

As a result, government figures for 2024 due in March, which will take into account all power sources, may differ slightly from Neso’s data. But the direction of travel is clear.

Back in 2014, wind and solar accounted for around 10% of Great Britain’s electricity. That has now risen to about a third, according to Neso’s figures.

Over the same period, fossil fuel generation has fallen by more than half.

That is mainly thanks to a sharp fall in coal generation – the dirtiest fossil fuel – with the UK’s final coal power station closing in 2024. Gas generation has also begun to decline.

This has helped to significantly clean up Britain’s power generation.

In 2024, each kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity generated 124g of planet-warming carbon dioxide on average – a new low, and down from 419g/kWh in 2014, according to Neso.

But gas remains a crucial part of the UK’s electricity mix, helping to maintain power supply when output from weather-dependent wind and solar sources drops.

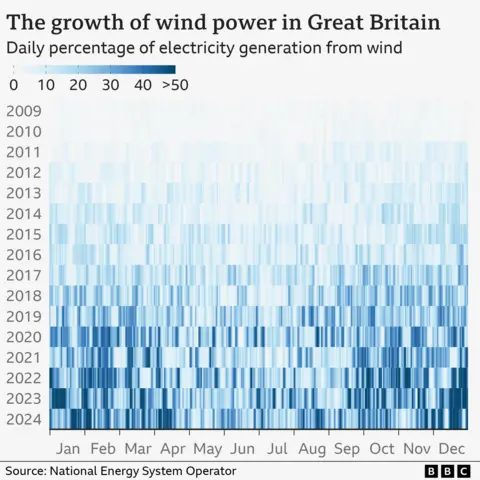

Britain’s wind turbines can generate huge amounts of electricity when weather conditions are right, as shown by the darkest blue in the chart below.

On around 10 days in December alone, more than 50% of Great Britain’s electricity generation came from wind.

However, there are of course less windy periods when electricity generation from wind drops. In the longer term, these gaps could be filled using emerging green technologies, such as batteries, to store energy during windier times.

There could also be extra incentives for people to use electricity during windy periods, for example by offering cheaper prices.

But for now, gas power stations, a ready source of on-demand energy, need to be fired up to fill the gaps. For three consecutive days between 11-13 December, for example, more than 60% of electricity generation came from gas as wind output dropped.

In its plan for meeting the 2030 clean energy target published last month, the government committed to keeping a reserve capacity of gas power stations for this purpose.

Last month Claire Coutinho, Conservative shadow secretary of state for energy security, said Labour’s “rush” to decarbonise the electricity system by 2030 would push up electricity prices and cause more hardship for people across Britain.

“We need cheap, reliable energy – not even higher bills,” she said.