FICTION

The Edge of the Alphabet

Janet Frame, foreword by Catherine Lacey

Fitzcarraldo Editions, $26.99

All you need to do is read the third volume of Janet Frame’s autobiography The Envoy from Mirror City to discover how The Edge of the Alphabet translated into fictional form Frame’s own loneliness in postwar London.

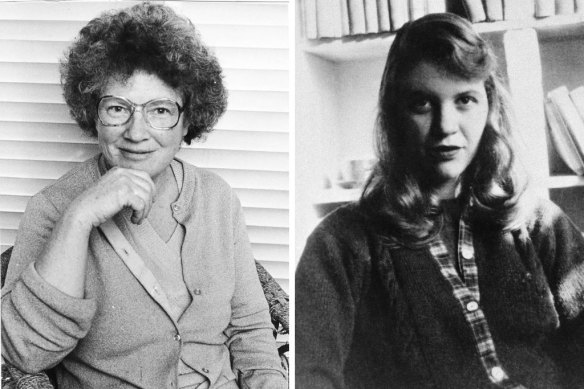

First published in 1962, when Frame was in her 30s and in and out of psychiatric facilities, The Edge of the Alphabet is a composite of her own exile. Like Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar in its malaise and encouraging of pseudo-biographical interpretation, Frame’s third novel is one of the great portrayals of depression, written at a time before mainstream pathologising, before we found a common language that so often flattens the specific textures of a depressive episode, a time when these darker states existed, in Frame’s words, “on the outskirts of communication … at the edge of the alphabet”.

Janet Frame, left, and Sylvia Plath wrote two of the world’s greatest explorations of depression.

Fitzcarraldo Editions, every cool kid’s favourite indie press, has republished this novel to commemorate the centenary of the writer’s birth. It takes three wayward characters – Toby, Zoe and Pat – on a voyage from New Zealand to London in search of better futures. What they discover instead, however, are new levels of spiritual poverty, an entrenched class system, menial jobs, solitude and indifference.

Toby Withers, who first appeared in Frame’s debut Owls Do Cry, is an epileptic, semi-literate outsider who leaves his home in New Zealand for “overseas” to write a novel about “The Lost Tribe”. This novel, we soon recognise, will remain forever unwritten — it’s an imaginary castle built in the sky, where Toby can house all his frustrations at his failure to communicate his interior life. Despite the anthropological suggestion of the title, Toby’s lost tribe isn’t “out there”; it is lost somewhere within himself.

Kerry Fox played Janet Frame in the 1990 film An Angel at My Table.

On the way to London, Toby meets Zoe Bryce and Pat Keenan. Zoe, a former schoolteacher and perennially seasick, receives her first kiss from an unknown sailor. On British shores, she buys an encyclopaedia of sex and imagines a different life, one that involves the love of another. “A year in the Antipodes,” Zoe reflects, “eleven thousand miles there and back in search of what most people find in the next room or, closer, in the lining of their skin”.

Pat, a mercurial Irishman, takes Zoe under his care, but is too caught up in the moral order of the times. The more Pat yarns about his nostalgia for Ireland and the vileness of British colonialists, the hollower this romantic vision appears. Each of them struggle to understand themselves in the shadow of homesickness, the urban desolation, and desynchronised social lives.