Alcoholic drinks should carry a label warning consumers about their cancer risks, the U.S. surgeon general said in an advisory on Friday, noting that their consumption increases the risk of developing breast, colon, liver and other cancers.

U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy also called for the guidelines on alcohol consumption limits to be reassessed so that people can weigh the cancer risk when deciding whether or how much to drink, alongside current warnings on birth defects and impairment when operating machinery.

“Alcohol consumption is the third-leading preventable cause of cancer in the United States, after tobacco and obesity, increasing risk for at least seven types of cancer,” Murthy’s office said in a statement accompanying the new report.

It is responsible for 100,000 U.S. cancer cases and 20,000 cancer deaths each year, more than the 13,500 alcohol-associated traffic crash deaths, it added.

There’s overwhelming evidence that alcohol causes cancer, and yet most people are unaware of the risks that come with drinking even a small amount. CBC’s Ioanna Roumeliotis breaks down the latest information and the growing push for mandatory warning labels.

In the U.S., there are about 20,000 alcohol-related cancer deaths annually, according to the report.

Alcoholic beverages in the United States currently carry a health warning label that advises pregnant women to not drink them and that their consumption impairs a person’s ability to drive a car or operate machinery.

This label has not changed since its inception in 1988.

“The direct link between alcohol consumption and cancer risk is well-established for at least seven types of cancer … regardless of the type of alcohol (e.g., beer, wine, and spirits) that is consumed,” the statement said, including cancers of the esophagus, mouth, throat and voice box.

The new report recommends health-care providers should encourage alcohol screening and treatment referrals as needed, and efforts to increase general awareness should be expanded.

Risks for ‘even a small amount of alcohol’

In early 2023, World Health Organization experts, writing in The Lancet, warned that even low levels of alcohol consumption come with the risk of getting cancer.

New proposed guidelines from the organization that advises the Canadian government on alcohol consumption dramatically reduce what’s considered low-risk drinking, suggesting no amount of alcohol is safe.

That same year, the organization that advises the Canadian government on alcohol consumption, the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, updated its guidelines on consumption, with recommended limits considerably lower than the 10 drinks a week for females and 15 drinks for males that were recommended in 2011.

The centre presented a new continuum, defining a low health risk associated with alcohol consumption as two or fewer standard drinks a week.

Its report on the guidelines said, “We now know that even a small amount of alcohol can be damaging to health.”

It said three to six drinks a week carry a moderate risk of negative health consequences — and seven drinks or more a week also increases the risk of heart disease or stroke “significantly.”

In a report issued in 2022, the organization said having more than more than six drinks per week leads to an increased risk of a host of health issues, including cancer.

For women who have three or more drinks per week, the risk of health issues increases more steeply compared to men, that report said.

Two papers published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal address the problem of high-risk drinking — one on how often alcohol use disorder goes unrecognized and offers guidelines for treating it, the other showing that certain kinds of antidepressants can drive some alcohol users to drink more.

“The reason why previously the guidelines were higher is that there was this conception that alcohol had some benefits with regard to some cardiovascular diseases,” Catherine Paradis of the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction told CBC News after the new guidelines were released.

“More recent studies now find that that is probably not the case,” she said.

Paradis said health warning labels are necessary to help Canadians be aware of the risks.

Sen. Patrick Brazeau, a recovering alcoholic, has put his support behind a bill for mandatory warning labels on alcohol. He says the public deserves to know the dangers, but the industry is pushing back.

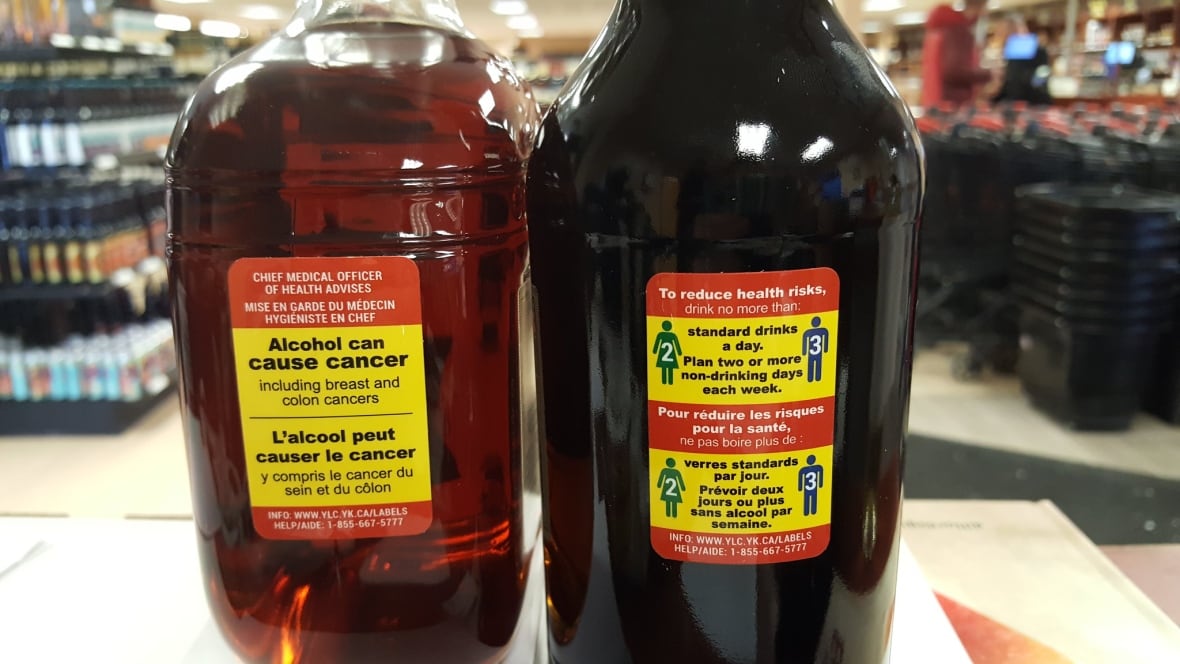

In 2017, researchers ran a pilot project in Yukon, funded by Health Canada, to study the impact of warning labels on bottles of alcohol.

Erin Hobin, senior scientist at Public Health Ontario who led the experiment, said it found sales of labelled products dropped by over six per cent at the government liquor store in Whitehorse that took part, compared to the jurisdiction the team used as a control that didn’t receive the labels.

Researchers placed three different labels on alcohol containers at the store. The labels warned that alcohol causes certain types of cancer, the number of safe drinks in a container and information on safe levels of alcohol consumption.

“My colleagues at Public Health Ontario and at the University of Victoria have been studying the importance of the impacts of cancer warnings on alcohol containers for over 10 years,” Hobin told CBC News on Friday.

“So we are very pleased and excited that high-profile public health and policy leaders are starting to now recognize the importance of cancer warnings on alcohol containers,” she said.