Thirty-three years ago, India’s mild-mannered Finance Minister delivered a startlingly bold Budget to the nation with the memorable words, ‘No power on earth can stop an idea whose time has come.’ The idea he was advancing was that of the liberalisation of the Indian economy, and the reforms he ushered in proved almost revolutionary, lifting many of the controls of the ‘licence-permit-quota Raj’ and transforming India’s derisory ‘Hindu rate of growth’ from below 3 per cent to a galloping, even tigerish, 8 per cent plus in the decade-and-a-half that followed.

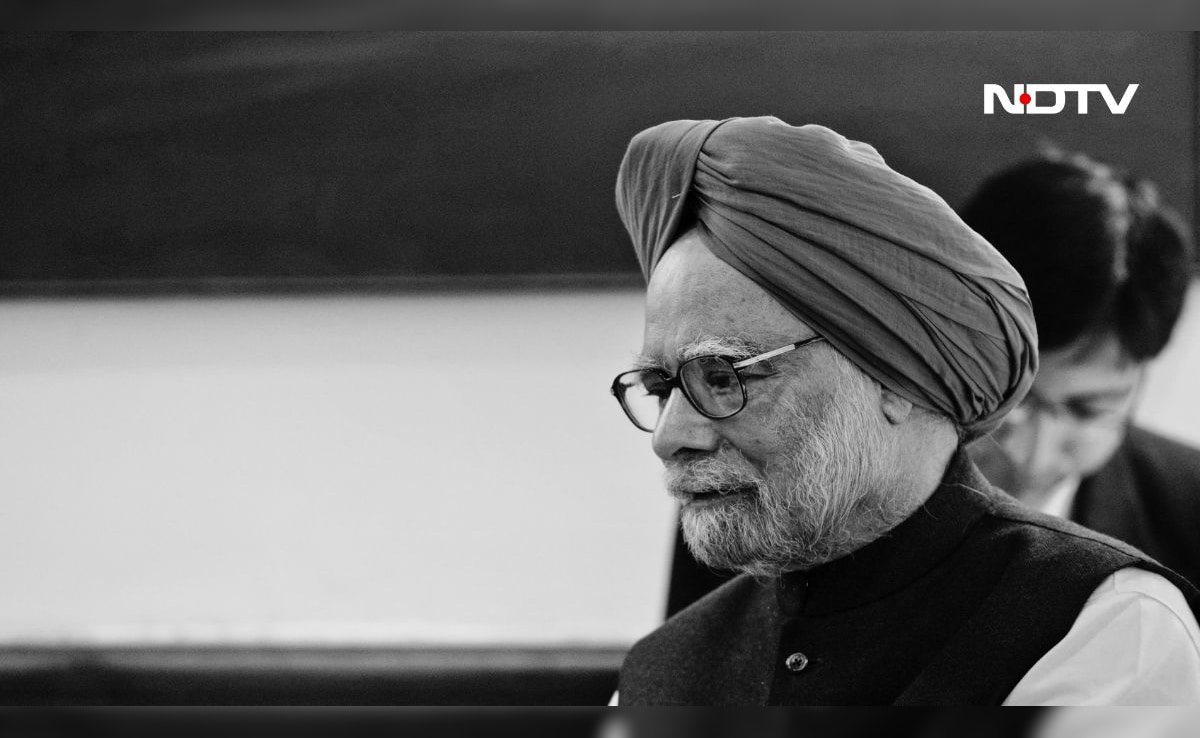

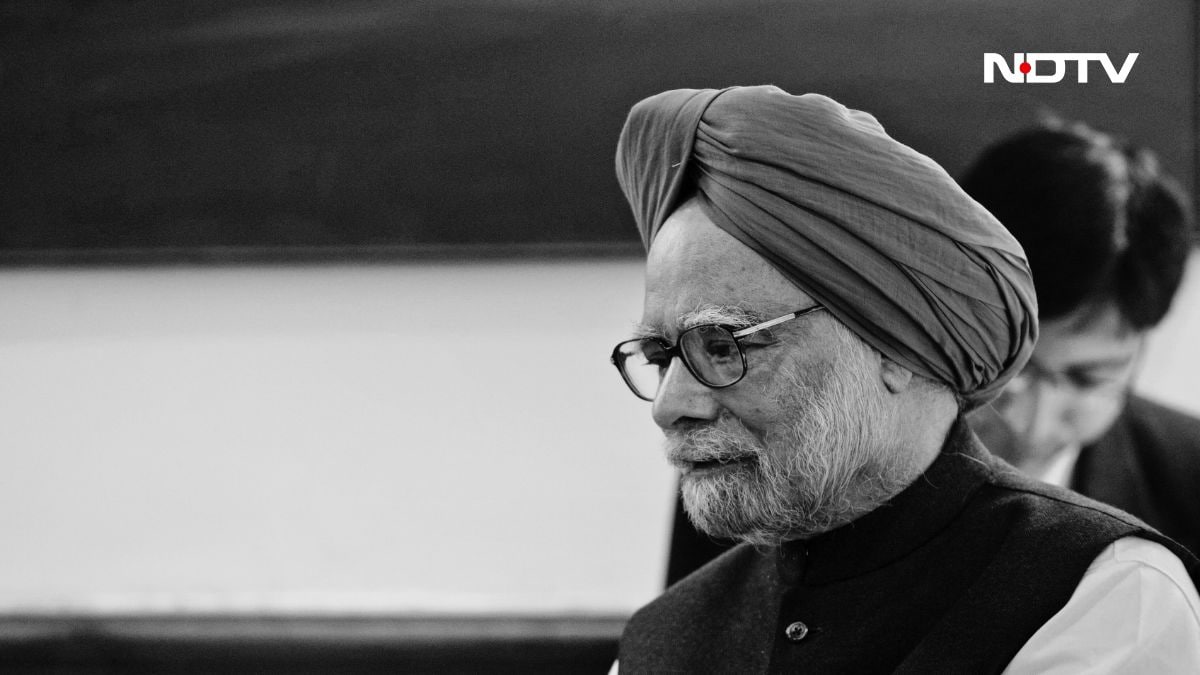

Today, that finance minister, and later prime minister, has passed into history. Among the obituaries lamenting his demise, and the encomia recording his services to the nation, come the inevitable reminders, especially on WhatsApp, of the derision once cast his way by his political critics, accusing him of indecision, pusillanimity and presiding over ‘policy paralysis’ while corrupt colleagues allegedly made off with the nation’s silver. His mildness dismissed as timidity, his calm and unflappable manner excoriated as complacency and ineffectiveness, his decency praised by critics damning him with faint praise, he is blamed for not being the kind of leader his critics claim he should have been.

Dr Singh Deserves Better

So as the page turns on the Manmohan Singh chapter, are his critics being grossly unfair? Or was he right to say, in 2014, “I honestly believe that history will be kinder to me than the contemporary media, or for that matter, the Opposition parties in Parliament”?

This is the same man who did more than anyone to earn our country a worldwide reputation as the world’s emerging big economic success story. Yes: Manmohan Singh deserves better.

For one thing, we are all living in an India transformed by his path-breaking initiatives. Manmohan Singh’s economic accomplishments were extraordinary. The India he took by the scruff of the neck in 1991 was an inefficient and under-performing centrally-planned economy which for forty-five years had placed bureaucrats rather than businessmen on its ‘commanding heights’, stifled enterprise under a straitjacket of regulations and licenses, thrown up protectionist barriers and denied itself trade and foreign investment in the name of self-reliance, subsidised an unproductive public sector and struggled to redistribute its poverty. Today’s India boasts a thriving, entrepreneurial and globalised economy with a dynamic and creative business culture, dealing with the world on its own terms. The contrast is extraordinary—and no one deserves a greater share of the credit for this transformation than Manmohan Singh.

Even as the planet faced an unprecedented global economic crisis and recession in 2008-09, India weathered the worldwide trend and remained the second-fastest growing major economy in the world after China—at a time when most countries suffered negative growth rates in at least one quarter in those difficult years. Manmohan Singh’s stewardship had a lot to do with this. His was the voice heard with greatest respect when the G-20 gathered to discuss the world’s macro-economic situation. “When the Prime Minister speaks, the world listens,” President Barack Obama observed, mentioning him first amongst the top three world leaders he admired.

A Far-Seeing Leader

Manmohan Singh’s ten years as Prime Minister pulled 10 million people out of poverty every year, saw the opening of millions of new bank accounts, the strengthening of rural purchasing power through the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, and the flourishing of lakhs of new small, micro and medium enterprises, particularly in the services sector. He introduced the Aadhaar scheme that today gives a digital identity to every Indian and has enabled the country’s much-lauded “Tech Stack” to be built. Insightful, a good listener and always quick on the uptake, he came up with dozens of new ideas and initiatives, some of which (like the creation of post-office savings banks and the initiation of direct benefits transfers) have endured and others (like GST and simplified direct taxation) were only thwarted by a cussed Opposition.

Of course, Dr Singh’s India had problems and challenges: the point is, were we on course to overcome them? Manmohan Singh was not guilty of either complacency or inaction. He had taken the measure of India’s major problems and devised far-seeing, practical and effective remedies to overcome them. From the Right to Information Act, which empowered the citizenry and made public officials more accountable, to the Right to Education Act, which brought a record number of children to school and pumped resources into moribund classrooms, his governance changed the face of our society.

The Manmohan Doctrine

In foreign policy, he propounded the Manmohan Doctrine, which saw India’s engagement with the world principally as a means to enable its own domestic transformation. Thus, he prioritised India’s relations with countries that could invest in our economy, countries that could supply us energy and countries that could enhance our food security. Not for him the grand flourish of strutting about on the world stage – in his quiet and understated way he opened us up to foreign relationships that could benefit our people. Ambassadors used to making grandstanding speeches and cultivating political contacts at cocktail parties and diplomatic receptions were told to refocus their efforts on facilitating trade and investment. There were fewer photo-ops and more concrete agreements.

The real picture of India’s clear progress under Dr Singh, in the face of myriad challenges, is far removed from the biased portrayal of a government beset by inaction and failure. Yes, corruption did exist, but it’s an Indian problem, not a problem to be blamed on Manmohan Singh alone. Corruption has been endemic despite, before and beyond his Prime Ministership. Though many of the lurid newspaper headlines about corruption on his watch proved untrue or grossly exaggerated, the allegations that fuelled them were at least proof of Indian democracy at work—institutions like the Comptroller and Auditor-General, the judiciary, the media and civil society functioning with fierce independence and passion, and without the heavy hand of government seeking to curb or stifle them. And the irresponsibly destructive behaviour of his Opposition did more to foment the worst perceptions about India’s performance as a nation unready for the opportunities of the 21st century than any of his government’s alleged failures.

Beyond Narratives

A more accurate and balanced portrayal of the Manmohan Singh legacy would look beyond the preferred narrative of the current powers-that-be, of an “accidental Prime Minister” presiding over an unscrupulous and ineffective government, to that of a visionary statesman who brought the India story to the centre of the world stage as the planet’s fastest-growing free-market democracy, and whose soft-spoken expertise commanded the respect of his peers.

Manmohan Singh transformed India, and did so with an uncommon level of integrity, personal incorruptibility and simple decency that were wholly admirable and moved all who had the privilege of knowing him. As one of those who had that privilege, I bow my head in pranaam to a truly great soul. He exalted every Indian through his service, and for that we should be eternally grateful.

(Shashi Tharoor has been a Member of Parliament from Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, since 2009. He is a published author and a former diplomat)

(Disclaimer: These are the personal opinions of the author)