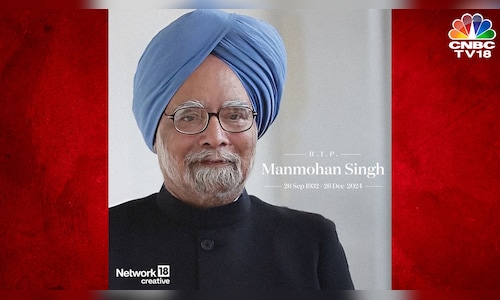

By the time he passed away, India itself had grown akin to an angry and aspiring adolescent, which is contemptuous of the previous generations’ failings, irreverent towards experience, and oblivious to its own frailty.

However, the man soldiered on against a vicious public attack, spoke his mind on important national issues, in his own time and on his own terms. There is a lot that he said in his more than half a century long career as a public servant and a thought leader, but it is no surprise that his most famous quote will be, “history will be kinder to me than the media.”

For an average Indian, any one of the following positions would be a dream come true. Singh, despite his humble beginnings, held many such dream chairs and left his mark in each of those offices.

| Year(s) | Position |

| 1957-1959 | Senior Lecturer, Economics, Punjab University |

| 1959-1963 | Reader in Economics, Punjab University |

| 1963-1965 | Professor of Economics, Punjab University |

| 1966-1969 | He worked at the UNCTAD Secretariat in Geneva, Switzerland |

| 1971-1972 | Economic Advisor, Commerce Ministry |

| 1972-1976 | Chief Economic Advisor, Finance Ministry |

| 1976-1980 | Secretary, Finance Ministry |

| 1980-1982 | Member, Planning Commission |

| 1982-1985 | Governor, Reserve Bank of India |

| 1985-1987 | Deputy Chairman, Planning Commission |

| 1987-1990 | Secretary General, South Commission in Geneva, Switzerland |

| 1990-1991 | Advisor (Economic Affairs) to Prime Minister |

| March-June1991 | Chairman, University Grants Commission |

| 1991-1996 | Finance Minister |

| 1998-2004 | Leader of Opposition, Rajya Sabha (Upper House of Indian Parliament) |

| 2004-2014 | Prime Minister of India |

That, after over six decades in public view, and holding so many positions in the government, Manmohan Singh managed to maintain an image that was more of an academic than a politician, or a power broker, says a lot about his ability to keep the spotlight on the issue at hand and not on himself.

Singh had no delusions of grandeur about his achievements either. Even as he got the accolades for sealing the India-US nuclear deal, he was ready to share credit with his rival where it was due. ‘I have only completed what you began,’ Singh told his predecessor at the Prime Minister’s Office, Atal Behari Vajpayee, as documented by Sanjaya Baru’s book ‘The Accidental Prime Minister’.

He wasn’t a complete pushover either, as many in India would like to believe, for much of his career. Despite carrying no political weight, Singh could threaten a resignation — and he did one too many times — and prevail over seasoned politicians across party lines and the many cabals within his party: the Indian National Congress.

| The many times Singh threatened to, or actually did, resign |

| 1985: Singh resigned as RBI Governor after a disagreement with the then Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee. Singh had proposed a scheme to allow NRI investments in India which the Late Mukherjee opposed. Pranab Mukherjee, in his own book, denied any role in Singh’s ouster from RBI. |

| Aug 1991: When the government was accused of favouring a bank with dubious credentials, Singh was the Finance Minister |

| March 1992: Singh was attacked by Congress colleague Arjun Singh, who was actually targeting the then Prime Minister Narasimha Rao. Both Rao and Singh stayed on. |

| December 1993: After a parliamentary committee criticised the Finance Ministry’s handling of the Harshad Mehta scam. |

| 2008: He resigned after members of the Congress party tried to stall the India-US nuclear deal. He prevailed and the historic deal for civil nuclear projects went through. Montek Singh Ahluwalia reportedly persuaded the Prime Minister to withdraw his resignation. |

Source: The Accidental Prime Minister, Author: Sanjaya Baru

‘No power on Earth can stop an idea whose time has come’ — Manmohan Singh said during his first budget speech in the Parliament as Finance Minister in 1991.

Manmohan Singh is credited with the sweeping reforms of 1991 when India opened its doors to global capital. But he was pushing the envelope long before that. “…he had articulated decades ago in his doctoral thesis, on the importance of foreign trade and greater openness to the world economy in India’s own development. No Indian policymaker had till then held South Korea up as a role model,” Baru wrote in his book.

He watched everything — from the Emergency in 1970s to the anti-Sikh riots, the assassinations of Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi, stock market scams from the 1990s to now, the chaotic era of political coalitions to the emergence of India as a nuclear power in the new century, as well as an array of scams from oil for food in Iraq to cash-for-votes in India, from the 2G spectrum scam to Commonwealth Games and coal allocation scam — and he was in the thick of things.

Very few have survived long enough to see all history unfold from such close quarters and even fewer would emerge such few bruises, after a long public life.

His untainted image spiralled down only in the final decade and a half of his life when he became the punching bag for the opposition parties and the media as scandals tumbled out of the closet in a government that he led. Yet, the worst allegation against him is that he turned a blind eye when wrongs were committed around him.

One could argue that he had never taken political responsibility before 2009. The success of single-handedly pushing through the India-US nuclear deal, possibly, gave him the credence and the confidence that would shape his career thereon.

He has never gone on record explaining the choices he made, whether it was to silently remain the Prime Minister while Congress President Sonia Gandhi and her trustees called the shots, or surrender his persona to enable a transition for Rahul Gandhi to emerge as a national leader.

Baru called it a ‘fatal error of judgement’ much like Bheeshma — from the Indian mythology, Mahabharata — a patriarch, who could choose his time of death, lived through generations ‘defending a disreputable lot’ , and suffered with them, with a false sense of righteousness.

‘The Accidental Prime Minister’, a book written by former journalist and Singh’s media advisor Sanjaya Baru, gave us a candid glimpse into the heart and mind of the statesman. “None of my predecessors in the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) has ever written a full account of his time there,” Baru wrote in the introduction. It could have been written by Singh himself.