Even after 23 years, Kelly Edwards stills loves being a paramedic.

“It’s very unpredictable. It’s exciting,” she said. “You meet a lot of nice people.”

But she admits there’s a much darker side to the job, too.

Edwards recalls a time she and her partner were treating an agitated patient. That patient threw a piece of furniture at her partner, breaking his arm.

“That was super uncomfortable, unacceptable,” the Ottawa paramedic said.

Edwards said she’s also been hit, kicked and spat on numerous times throughout her career. That’s on top of the verbal abuse and sexual harassment she faces daily.

“I’ve heard lots of threats of being sexually assaulted and descriptions on how they do that,” said Edwards. “It’s pretty uncomfortable when you’re in the back [of the ambulance] or you’re alone with that patient.”

It’s a reality that not only affects women in the job. Mathieu Roy, who’s been with the Ottawa Paramedic Service for more than 22 years, said his safety “is put on the line pretty much on every call.”

“Being told, ‘I will kill your family’ when I meet [patients] is something that occurred more than once in my career,” he said.

Marc-André Périard, vice-president for the Paramedic Chiefs of Canada, said stories like these have become a regular occurrence for paramedics across the country.

“A lot of the … public aren’t aware that this occurs frequently. They think it’s an anomaly,” he said.

Gaps in the data

Périard said the problem only seems to have gotten worse over the years, but any details are mostly anecdotal.

Experiences of violence are significantly under-reported, according to Périard, because there is no standardized complaint system for working paramedics. Every service has their own culture and system, he said.

That also means there’s no data available that accurately quantifies what the approximately 40,000 paramedics in Canada are up against while they’re at work, according to Renée MacPhee, an associate professor at Wilfrid Laurier University who has focused on paramedic research over the last 30 years.

“We don’t have a fulsome picture. We don’t know how big the problem is,” said MacPhee.

Most research on the topic has been conducted in the U.S. and other countries, she said, with just a handful of jurisdictions in Canada including Saskatchewan, Manitoba and a few paramedic services in Ontario collecting their own data.

Researchers like MacPhee have been able to glean some consistent details from the available research, and it confirms that paramedics are consistently experiencing physical abuse, verbal abuse and sexual assault while on the job.

Some research shows the impact this has on the mental health of those in the job.

According to a 2018 study done by the Canadian Institute for Public Safety Research and Treatment, paramedics had the highest likelihood of developing suicidal behaviours among nearly 6,000 public safety personnel surveyed.

National survey the first of its kind

It’s something that the Paramedic Chiefs of Canada (PCC) hopes to better understand — and change — with an upcoming national survey in partnership with MacPhee’s research team, described as the first of its kind in the country.

The survey, funded by Defence Research and Development Canada, is set to roll out in the new year. It will be issued to paramedics across the country in the hopes of painting a fuller picture of what paramedics are up against, and give insight into how to better protect them.

“I think we’re going to be quite unpleasantly surprised with the amount of violence that has actually happening, and I don’t think the public is even remotely aware that this is happening,” said MacPhee.

Researchers will interview as many paramedics across Canada as possible over the course of six weeks. Questions will focus on personal experiences of violence on the job, how paramedics are being trained to defend themselves, and the impacts violent encounters have on personnel and their families.

“It’s definitely changed me,” said Edwards of her time on the front lines. “It makes me less trusting of people. I know there’s good people out there, but I definitely find myself apprehensive.”

Evidence of violence could bring change

Périard and MacPhee said the hope is to use the results of the survey as a tool to better advocate for change and ultimately make it safer for those in the profession.

“These are people who have dedicated their lives to caring for every single Canadian in this country, and to see them victimized as part of that job is heartbreaking,” she said.

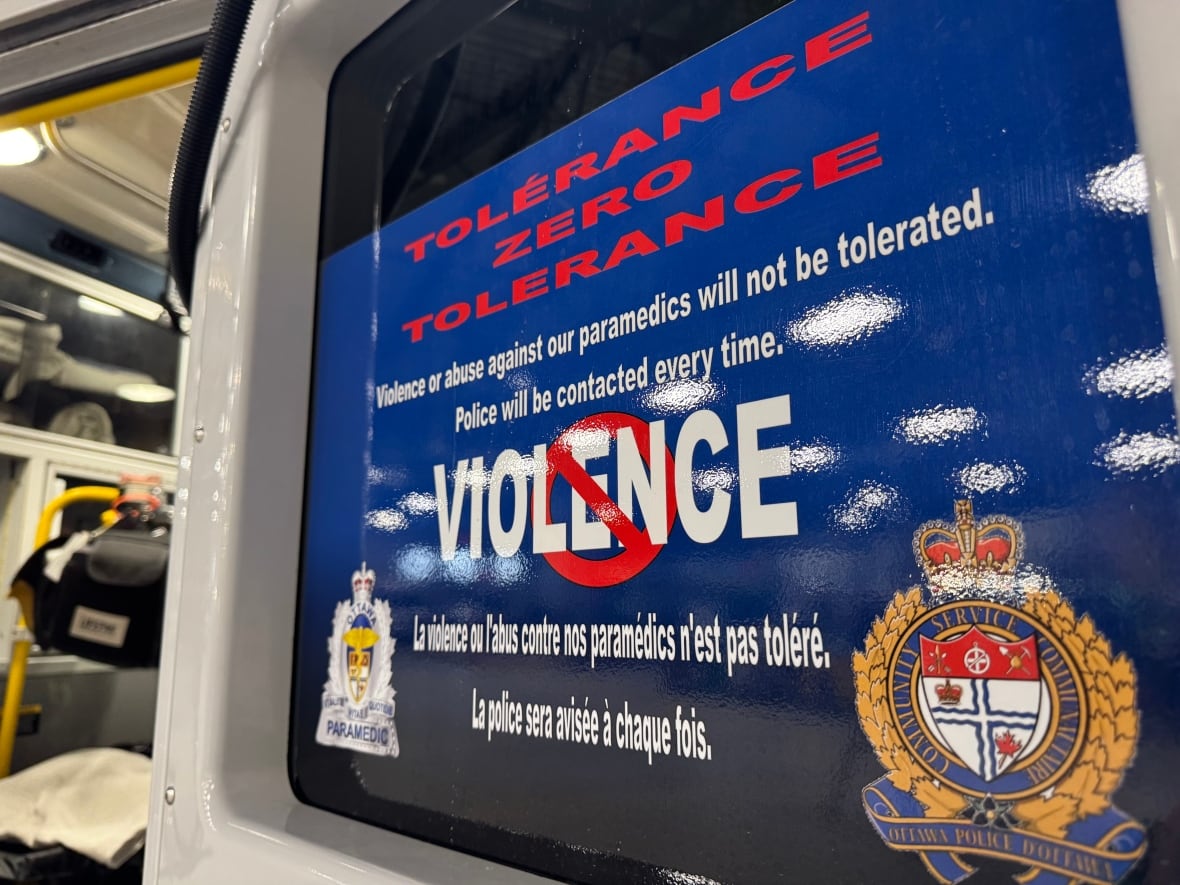

The PCC has advocated for royal assent of Bill C-321, which looks to amend Canada’s Criminal Code to introduce harsher penalties for assaulting a health-care worker or first responder. It passed third reading in the House of Commons in February, but has been stalled since.

The bill was recently discussed at a Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs.

A report from committee chair Brent Cotter acknowledged “that there is a serious and growing increase in acts of violence against first responders,” but added that “this bill aims to increase penalties without addressing the underlying systemic and societal issues that contribute to increases in these forms of assaults.

“Without such measures, criminal law changes risk resulting in further overrepresentation in the criminal legal system of those most marginalized,” wrote Cotter.