Much of the detail he shares about them is already woven into the fabric of their legend. Their obsession with their weight. Their terror of surveillance and deportation. Their anguishes about children lost and unborn. His love of pot; her preference for cocaine and heroin. Her grip on the purse strings; his churlish resentment of Elvis, Dylan and Jagger.

Beatles fans might relish a close-up look at a Christmas Day reunion between the Lennons and McCartneys in the late ’70s. Still, it’s difficult to credit Mintz’s insight when he’s effectively just peering through the keyhole at such a long, emotionally loaded relationship.

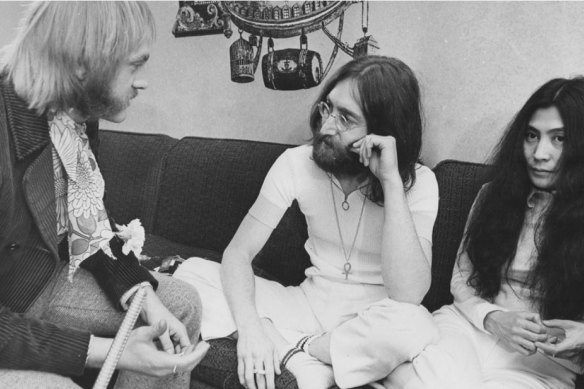

Australian journalist Ritchie Yorke interviewing John Lennon and Yoko Ono in 1969.Credit: Ritchie Yorke Collection

There are barmier revelations too, such as the invisibility incantation John and Yoko would use before walking through public spaces. If they fully and intently believed they were the Reverend Fred Gherkin and his wife, crowds would think so too. Miraculously it worked, writes Mintz, “until it didn’t”.

The oft-told “lost weekend” episode, in which Ono banishes her unfaithful husband to a year of debauchery in Los Angeles, is naturally rendered more colourful by the man she charged to “keep him safe”. The particulars of its sordid climax might shock some fans of the working-class hero, but it’s really only another smudge against the infamously flawed character of a profoundly damaged superstar.

“They were paradoxes,” Mintz writes. “They could be incredibly sensitive, honest, provocative, caring, creative, generous, and wise” but also “self-centred, desperate, vain, petty, and annoying”. He adds: “In John’s case, also shockingly cruel.”

Loading

Unsurprisingly, the author emerges from his story as an utterly selfless, loyal and discreet appendage to the vilified, worshipped, eccentric and delusional couple at the centre of their own cosmically arranged circus. We never find out why he’s now chosen to break the sacred bond of silence which was always understood, if not specifically stated, as a crucial condition of their friendship.

Lennon, of course, is long gone. But “Yoko needed me more after John’s death,” Mintz writes, “and I also became an employee and official spokesman of the estate” — not to mention, no doubt, keeper of secrets that might detract from what remains a living and highly lucrative legend.

Perhaps Yoko Ono, after weathering six decades of open abuse and implicit scorn from the overwhelming majority of those who know her name, is at last beyond caring. Considering the unique and unprecedented madness of the life described here, it’s virtually impossible to know what to think anyway.