I once spent a day with John Marsden at his alternative school, the Candlebark School in the Macedon Ranges. He showed me around, we talked privately, and I sat in on a couple of his classes. I was impressed by this tall broad man who didn’t want to come across as an authority figure, yet still had a natural authority.

He was eager and passionate about teaching and rearing young people, particularly boys, and confronting them with risk and adventure. You could see the kids both loved and respected him and felt free to approach him. As we walked around the school, he stopped frequently for a one-on-one chat with a student, giving that young person all his attention.

Marsden in the library of the Alice Miller secondary school in Macedon in 2016.Credit: Alex Ellinghausen

During one class, he gave everyone a creative writing exercise: write about a beautiful view of a lake from the point of view of someone who’s miserable and angry. I hope I’ve remembered that correctly. I tried the exercise too, and it was really hard.

All that passion, energy and commitment flowed into his books. When he died last week at 74, still at work, he left more than 40 of them, mostly aimed at teenage readers. A common theme is teens learning to weather dire physical and emotional challenges.

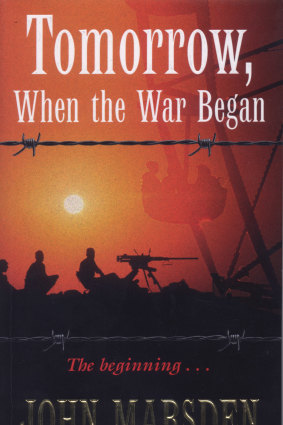

The first book in Marsden’s seven-book Tomorrow series.

These books have sold in their millions around the world. He won every accolade going for Australian young adult books and a few international ones as well. It’s no exaggeration to say that our current YA fiction, which has flourished and expanded so much in recent years, was kick-started by Marsden’s work and influence.

You have to go back into Marsden’s own childhood and adolescence to see where this comes from. A bad school experience and an alienating time at university led to a breakdown, and he needed years of therapy to recover.

Once I sat in a Melbourne Writers Festival audience while he revealed his father often used to beat him with a length of black hose. Then one day when he was about 14, he decided he wouldn’t take it any more. “He told me, ‘Go to your room’ … and I said, ‘I’m not going.’ A terrible scene followed, but I didn’t back down. And I’m glad I didn’t. It was one of the defining moments of my life.”

He went on to say he believed boys were engaged in a status battle with their fathers, and that the boys should win. “A good father will congratulate you. A bad father will find excuses, or get angry.”