BBC

BBCWhen Syrian rebel leader Ahmed al-Sharaa arrived in Damascus and gave a victory speech on the heels of a lightning military campaign that swept through the country and toppled Bashar al-Assad’s regime, one remark went widely unnoticed. That was his reference to an illegal narcotic that has flooded the Middle East over the past ten years.

“Syria has become the biggest producer of Captagon on earth,” he said. “And today, Syria is going to be purified by the grace of God.”

Mostly unknown outside of the Middle East, Captagon is an addictive, amphetamine-like pill, sometimes called “poor man’s cocaine”.

Its production has proliferated in Syria amid an economy broken by war, sanctions and the mass displacement of Syrians abroad. Authorities in neighbouring countries have struggled to cope with the smuggling of huge quantities of pills across their borders.

All the evidence pointed to Syria being the main source of Captogan’s illicit trade with an annual value placed at $5.6bn (£4.5bn) by the World Bank.

At the scale that the pills were being produced and dispatched, the suspicion was that this was not simply the work of criminal gangs – but of an industry orchestrated by the regime itself.

Weeks on from the speech by al-Sharaa (previously known by his nom de guerre of Abu Mohammed al-Jolani), spectacular images have emerged that suggest the suspicion was correct.

Getty Images

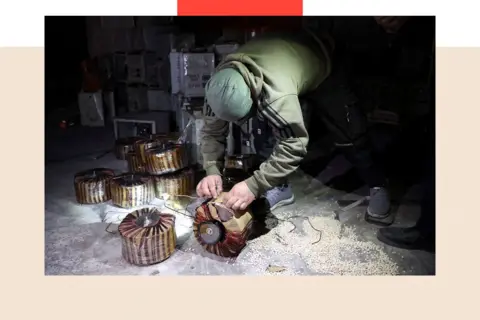

Getty ImagesVideos filmed by Syrians raiding properties allegedly owned by relatives of Assad show rooms full of pills being made and packaged, hidden in fake industrial products.

Other footage shows piles of pills found in what appears to be a Syrian military airbase, set on fire by the rebels.

I spent a year investigating Captagon for a BBC World Service documentary and saw how the drug became as popular among the wealthy youth of Gulf countries like Saudi Arabia as it was among the working class in countries like Jordan.

“I was 19 years old, I started taking Captagon and my life started to fall apart,” Yasser, a young male addict in a rehab clinic told us in Jordan’s capital, Amman. “I started hanging out with people who take this thing. You work, you live without food, so the body is a wreck.”

So how will al-Sharaa and his group, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), deal with the large number of people in Syria and around the Middle East addicted to Captagon who may suddenly find themselves without a supply?

Caroline Rose, an expert on Syrian drug trafficking at the New Lines Institute, has concerns around this. “My fear is that they will really crack down on supply and not necessarily try to do any sort of demand reduction.”

But there is a broader question at play too: that is, what effect will the loss of such a lucrative trade have on Syria’s economy? And as those behind it move aside, how will al-Sharaa keep at bay any other criminals waiting in the wings to replace them?

The narco-war in the Middle East

The proliferation of Captagon pushed the Middle East into a genuine narco-war.

While filming with the Jordanian army on their desert border with Syria, we saw how the soldiers had reinforced their fences and learned about their comrades who had been killed in shoot-outs with Captagon smugglers. They accused the Syrian soldiers across the border of aiding the smugglers.

Other countries in the region have been just as disturbed by the trade.

For a while, Saudi Arabia suspended imports of fruit and vegetables from Lebanon because authorities were frequently finding shipping containers full of produce like pomegranates which had been hollowed out and filled with bags of Captagon pills.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWe filmed in five countries, including in regime-held and rebel-held Syria, consulted well-placed sources, and gained access to confidential records from court cases in Germany and Lebanon.

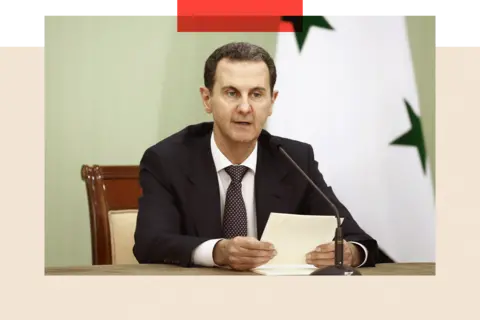

We were able to name two major parties as having their hands in the trade – Assad’s extended family and the Syrian armed forces, in particular its Fourth Division, led by Assad’s brother, Maher.

Questions surrounding Assad’s brother

Maher al-Assad was perhaps the most powerful man in Syria aside from his brother.

He was sanctioned by many Western powers for the violence he wrought against protesters during the pro-democracy uprising in 2011 that precipitated the bloody civil war. The French judiciary has also issued an international arrest warrant for him and his brother for their alleged responsibility in chemical weapons attacks in Syria in 2013.

Gaining access to the WhatsApp chats of a Captagon trader imprisoned in Lebanon, we were able to implicate Maher al-Assad’s Fourth Division and his second-in-command, General Ghassan Bilal.

The revelation was a huge milestone in confirming the role of Syria’s armed forces and Bashar al-Assad’s inner circle in the trade.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSeeing the recent images of demoralised Syrian army troops fleeing without a fight as the rebels advanced, I was reminded of an interview we conducted with a regime soldier last year.

He told us his monthly army pay of $30 (£24) barely covered three days of food for his family, so his unit became involved in criminality and Captagon.

“It’s what brings most of the money now,” he said.

In May 2023, the Arab League agreed to re-admit Syria 12 years after it was expelled for violently suppressing the popular uprising. It was seen as a diplomatic coup for Assad, using promises to tackle the Captagon trade as leverage to be rehabilitated.

Can the rebel leaders crack down?

Now, as Syria’s rebel leaders consolidate their power over the organs of state, it seems they are fully aware of positive signals they are sending to wary neighbouring states when they promise to crack down on the Captagon trade.

But it might be a steeper task for them to wrest the country away from a lucrative criminal enterprise after so many years when it was encouraged by the state itself.

Issam Al Reis was a major engineer in the Syrian army until he defected at the beginning of the uprising against the Assad regime, and has spent time investigating the Captagon trade. He believes that HTS will not need to do much to stop the trade initially “because the main players have left” and there’s already been a dramatic drop in Captagon exports – but he warns that “new guys” might be waiting in the wings to take over.

This will be particularly problematic if the demand side isn’t tackled too. There is little evidence of investment in rehabilitation from the time HTS controlled Idlib province in north-west Syria, according to Ms Rose. “[There was a] very poor picture for trying to address Captagon consumption,” she says.

She also says there has already been an uptick in another drug being trafficked through Syria.

“I think many users will seek out crystal meth as an alternative, especially users who have already established a tolerance to Captagon and need something that’s a bit more strong.”

The other problem, as Mr Al Reis points out, is a financial one. As he puts it: “Syrians need the money.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHis hope is that the international community will help prevent people entering the drug trade through humanitarian aid and easing sanctions.

But Ms Rose argues the new leaders will need to identify “new and alternative economic pathways to encourage Syrians to participate in the licit formal economy.”

While the kingpins have fled, many of those involved in manufacturing and smuggling the drug remain inside the country, she said.

“And old habits die hard.”

Additional reporting by George Wright

Top picture credit: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.