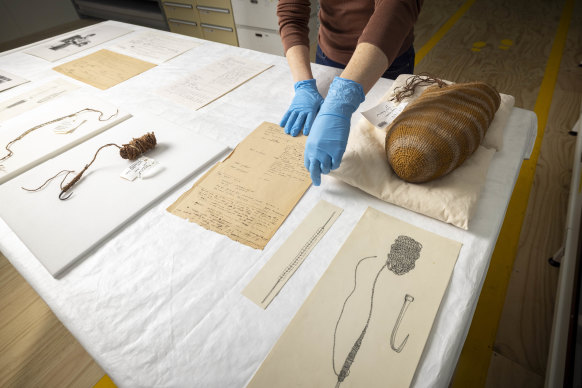

At a climate-controlled storage facility in Melbourne’s outer suburbs, stringybark spears rest in white corflute boxes. On a bench in front of us, a fishing hook from West Cape York made from turtle carapace sits next to a stack of notes with illustrations, and a photograph of the man who wrote them: Donald Thomson, nonchalantly handling a taipan on the Cape York Peninsula in 1928.

“He was a naturalist, a biologist, a zoologist, a botanist,” says Elaine Thomson, his daughter. He was also a vehement defender of Aboriginal rights. “He wanted to study people in their environment. To him, they were inseparable. You can’t know the people if you don’t know the environment in which they live, and what it means to them, and how it informs their history, and their social interaction.”

Professor Donald Thomson collected art and day-to-day items from Aboriginal communities through trade and gifts.Credit: Wayne Taylor

Elaine and her sister Louise Thomson-Officer have spent the last year working with the University of Melbourne to bring Thomson’s life’s work together.

In 1973, the family donated the first component of the collection, about 7500 artworks, weavings and cultural objects. Now, they’ve donated the rest – the UNESCO-inscribed Donald Thomson Ethnohistory Collection, an archive of thousands of pages of field notes, photographs and 7.6 kilometres of colour film, the detailed record of his work understanding and documenting Australia’s Indigenous cultures. As of this month, Thomson’s entire archive has been brought together for the first time in more than 50 years.

Donald Thomson first visited Cape York in 1928, where he met the Yintjingga people and, in Elaine’s words, “fell in love”.

“They were honest and generous and inclusive,” she says. “They let him into their lives, and adopted him as a family member. And these communities entrusted him with their culture.”

For the next four decades he spent long periods with Aboriginal communities in Cape York and Arnhem Land. He collected art and day-to-day items from these communities through trade and gifts. While petty theft and grave robbery were rife in the anthropological profession, Thomson was distinctly ethical and respectful.

Not only was he a witness to the depth of Indigenous culture and economic life, he saw firsthand their destruction and mistreatment. He documented violence, abuse and imprisonment, and dedicated himself to exposing and ending these practices.

When Elaine was a child at home in Melbourne, her mother would arrange airdrops of supplies to him in Arnhem Land.

Some of the artefacts from Donald Thomson’s collection.Credit: Wayne Taylor

“His love of the people was evident all the time,” she recalls. “As was his outrage at how they were treated.”

Thomson was outspoken in a time when advocating for Indigenous rights was, to put it lightly, not popular work. He was also well connected. Elaine later learnt that the “Bob” that her father often spoke of was prime minister Robert Menzies. They had a difficult relationship. Thomson felt that Menzies didn’t do enough to help Indigenous people.

In Victoria, he was involved in the Aboriginal Welfare Board, and sat on the board of the Lake Tyers Victorian Aboriginal Reserve in Gippsland. Lake Tyers was described by Thomson’s biographer Robert Macklin as “more like a prison than a home”, and Thomson fought hard to get conditions approved. He was ignored, and he duly resigned.

Downstairs in the university’s storage facility, there’s a collective intake of breath. We’re looking at century-old bark paintings, carefully preserved. One depicts a boat, illustrating the trading relationship between Arnhem Land and Makassar, a once-wealthy port, which is now part of Indonesia. It’s a relationship that long predates British colonisation.

Another is a design that is usually painted on the body, painted on bark for Thomson, for posterity. As with many items in the collection, the process of creation and the ceremonial use are the important bits. But the record is an invaluable tool for study.

While the artworks and objects have been in the university’s collection for decades, it’s Thomson’s extensive notes that give them context.

Professor Marcia Langton, an anthropologist and geographer from the University of Melbourne, says the collection is a link to millennia of cultural practices that were interrupted by colonisation.

“It’s highly likely that many objects in the collection have not been made for decades because of cultural and economic change in these communities,” she says. “If you can buy a metal fish hook and a fishing line for $30, why would you spend days making this beautiful hook?”

Langton is chair of the University of Melbourne’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cultural Heritage Oversight Committee. She and her team are developing a facility for visitors from Arnhem Land, Cape York and beyond to interact with and learn from the collection.

“Now, so many of these traditions have been revived, but people don’t understand the origins,” she says. “We’ve had requests from communities who say that we really need our young people to see these things, so they know what the old people did. It’s heartbreaking.”

Elaine says her father died believing he had failed in his life’s mission to improve conditions for the people he loved. After he died in 1970, his widow, Dorita, donated his object collection to the University of Melbourne. With the help of Museums Victoria, which ended up as caretaker, Dorita facilitated access to the objects, and sent out hundreds of photos and copies of material – which Elaine says her mother paid for.

“There’s a huge need for research,” says Langton. “There’s so much we don’t know about our collections. And we have to make sure that not only are communities of origin well informed, but that the Australian public have knowledge of this human cultural wealth.”

In May 2025, a selection of works from Thomson’s collection will form part of the exhibition 65,000 Years: A Short History of Australian Art at the Potter Museum of Art. Five decades after his death, his collection still has much to tell us.

“This is what my father wanted all along,” says Elaine. “This is for all Australians, as a teaching tool and trying to bridge the gap so to speak. That was the point.”

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.