Much of Michael Leunig’s prolific output was created, he once said, while “sitting alone, feeling lost, alienated from the world”. It was a state that he believed was essential to his creative process.

“I think humans come together and communicate on the basis of their aloneness,” he told filmmaker Kasimir Burgess in one of the many interviews the pair conducted over many years for the excellent 2019 documentary Fragments of Leunig. “A friend holds our aloneness, and we hold theirs. There’s some exchange of solitudes.”

For 55 years, Leunig’s cartoons and written musings in The Age, and later The Sydney Morning Herald, were offered as an exchange of sorts to vast swaths of loyal readers. To those who approached them in a state similar to that in which they were created, many did land as a form of solace, confirmation that we are not as alone in our solitude as we might imagine.

Leunig’s stock-in-trade was what friend and fellow media legend Phillip Adams called “weaponised whimsy”. His avatars, drawn in a thin quavering line, almost always with downcast head and oversized nose, passed through the world in a state that alternated between bewilderment and wonder, with side trips to despair and occasional forays into anger.

Vale LeunigCredit: Matt Golding

“He had two very different arms to his cartooning: his political cartoons on the one hand, and his social observations on the other,” said Patrick Elligett, the last of a long line of editors for whom he worked at The Age. “In some ways, he brought together those two polar opposite styles through his work.”

The degree to which Leunig connected with his audience was evident from the frequency with which fellow travellers might stumble upon a cartoon torn from the Saturday edition of the paper and affixed to the door of a friend’s refrigerator with Blu Tack, sticky tape or a magnet.

Though created for the most disposable of media, they sometimes stayed there for years, perhaps even decades, curling at the corner, yellowing with age, overlooked for long periods among the clutter of kinder drawings, plumbers’ magnetic cards and shopping lists. But when one day they again caught the eye, they would strike it as if for the first time. “Yes,” the beholder would think. “I know that feeling, exactly.”

Leunig liked to describe himself as a “cartoonist, writer, painter, philosopher and poet”, whose work “often explored the idea of an innocent and sacred personal world”. His musings – some of which he styled as “prayers” – were votive offerings to a largely secular readership. He invoked the idea of God, but not in an institutional or corporeal sense. “I just think it’s a poem, it’s a feeling,” he said on Andrew Denton’s interview program Enough Rope – for which occasion he turned up wearing sandals – “I just love the word … it sings, it’s sweet.”

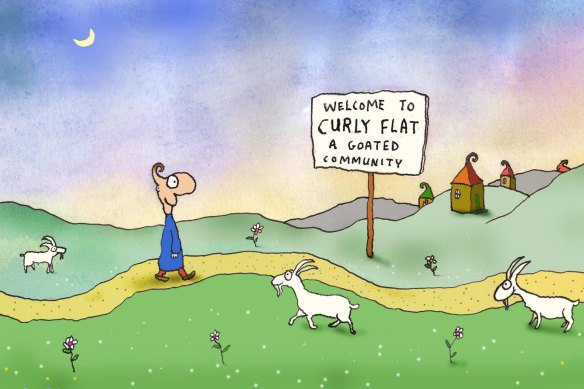

A cartoon featuring one of Leunig’s more beloved characters, Mr Curly.Credit: Michael Leunig

Leunig’s trademarks were gently drawn figures: Mr Curly, with his bouffant quiff; teapots, perched in the most unlikely places, but always offering the hope of ritual and respite from the madness of the world; the perennially searching Vasco Pyjama; his direction-finding Duck (so many ducks). But the gentle whimsy could be deceptive.

“On the surface, the cartoons, the drawings, the musings are often remarkably gentle,” observed Adams. “But by god, they’re also incredibly tough. And he can cut through the bullshit.”

Though known for his whimsy, Leunig “was also brave in the way of a warrior”, said Peter Ellingsen, a former colleague at The Age. “He saw, or sensed, hypocrisy and pricked its self-importance, which incensed those convinced of their rightness. His mind and heart worked together to uncover the rough edges we like to overlook. He knew that questions are always more interesting than answers.”

Or as the violinist and composer Richard Tognetti, who was a friend, said: “He draws you in with whimsy and then throws a punch.”

That duality in his work perhaps owed something to being a sensitive child raised in hard-scrabble circumstances. The eldest of five children, Leunig was born to a slaughterman father. He was educated at public schools in Footscray and Maribyrnong and, he claimed on his own website, “at various factory gates, street corners, kitchen tables, paddocks, rubbish tips, quarries, loopholes, puddles and abattoirs in Melbourne’s industrial western suburbs”.

He narrowly avoided being conscripted to the Vietnam War by dint of being deaf in one ear. Instead, he went to a different killing field, finding work in an abattoir.

Loading

To the filmmaker Burgess, he wondered if this hadn’t been a key, if unlikely, influence on his artistic practice.

“That was my art school in a way,” Leunig said. “There’s this life and death going on. If working in this way brutalises some people, it sensitises others. It certainly sensitised me.

“Maybe there’s death and there’s creation,” he added. “You create life in a way, something that’s life-giving. Maybe it’s a reparation for the fact of so much death.”

He’d had intimations of an artistic career long before the slaughterhouse. At primary school he was lucky enough to have a teacher, an Englishwoman named Joan, whose influence was both positive and profound.

“She did what teachers must do,” he told Burgess. “They want you to find who you are, and they lead you to that. She wasn’t trying to make me into something; she was allowing me to become myself.”

That self was both public and intensely private.

Though he was part of a stable of cartoonists at The Age that included fellow luminaries such as Ron Tandberg, Peter Nicholson and John Spooner, Leunig became far more of a brand name than any of his contemporaries. A one-man factory, his works were collected in books (at least 24, from the first collection, published by Penguin, in 1974), printed on mugs and T-shirts and tea towels, seconded for calendars and Christmas wrapping paper distributed via The Age in its broadsheet days.

Leunig contributed to this masthead until August, when his contract was terminated as part of a redundancy round in which a many journalists also departed.

But even during his years as a permanent staffer, he had retained an agent to negotiate a substantial additional cut of revenues from the marketing department, which funded all those spin-off products. And he valiantly resisted all efforts to renegotiate his salary in line with his declining journalistic output (in the end, he was producing just one cartoon a week for this masthead).

“He was a tough negotiator,” recalls a former executive who handled those discussions with him. “I used to love the negotiations – we shared a lot of the same values and thoughts about where society was heading – but he wouldn’t budge on his salary at all. He’d just say, ‘This is what I get.’ But it was always very entertaining.”

The steeliness beneath the apparently laid-back exterior perhaps offers a clue to the true Leunig. He saw himself as an outsider, and demanded to be heard. He bristled when an editor overruled a cartoon or column on grounds of taste or sensitivity, even though being “spiked” is simply part and parcel of a journalist’s working life. “Where is the valuable outsider perspective, the free thinker, the dissenting intelligent voice?” he once asked an editor in frustration.

He was estranged from various members of his family, and attended neither of his parents’ funerals, claiming he did not even know where they were buried. He was twice married – to his childhood sweetheart Pamela for about 20 years, and to photographer Helga Salwe, whom he met when he was 43, but from whom he separated some years ago.

Leunig had two children from each of his marriages, but for The Leunig Fragments only Sunny, from his first marriage, agreed to be interviewed. Revealing that he and his father lived on the same street, but that he would never knock on his father’s door, Sunny said: “He has definitely sacrificed his family and personal life for his art.”

Leunig’s first cartoon for The Age, produced as cover for Ron Tandberg, who was on leave, in 1969.Credit: Leunig

He strove in his work to give shape to what he called “the felt life … the raw truth of human feeling, whether it be about the subject of war or love or nature”. More often than not, he succeeded. But not always, and not with everyone.

On occasion, Leunig deployed his curvilinear style to tackle the most sharp-edged of subjects, and sometimes found himself in the crosshairs of public opprobrium. Appalled by Israel’s actions towards Palestinians long before this latest round of bloodshed, he drew a parallel between the Nazi labour camps and the West Bank with a two-panelled cartoon referencing the “Arbeit macht Frei” slogan that hung above the gates of Dachau, among other places. For that, he was labelled an antisemite by some critics.

In 1995, he drew a multi-panel cartoon under the heading Thoughts of a Baby Lying in a Child Care Centre. “Call her a cruel, ignorant, selfish bitch if you like, but I will defend her,” the swaddled infant said. “She is my mother and I think the world of her.”

Childcare was a theme he revisited often. In 2000, he sparked outrage with a picture of a drive-through creche (have ticket ready), and in 2019, the furore was even stronger when he depicted a pram-pushing mother losing track of her baby while her eyes are glued to her phone (“Mummy was busy on Instagram, when beautiful baby fell out of the pram”).

“A lot of women, including me, never forgave him [for Drive Thru Creche],” said one female journalist who worked closely with him for many years. “The view from the ivory tower and all that, a (very) high-earning man frowning on the choices of mothers who had no choice but to work.”

The Drive Thru Creche cartoon (2000) lost Leunig many fans.Credit: Michael Leunig

In 2021, he outraged many with a cartoon equating COVID anti-vaxxers with the student uprising of Tiananmen Square.

To academic Dr Robbie Moore, writing in the journal Meanjin that year, Leunig’s “journey from anti-war and anti-corporate provocateur to a critic of ‘wokeism’ and cancel culture” was both “familiar and predictable”.

But to former colleague Stephanie Bunbury, it came as no surprise at all. “We used to hang out quite a bit in the ’80s,” she said. “He was more conservative than his identification with Melbourne’s ’70s counterculture would suggest. I remember him telling me he didn’t like Monkey Grip because it showed people having sex.”

“I don’t want people watching me when I do that,” he told her, “so I don’t see why I should watch anyone else.”

It’s unlikely Leunig was too upset if his work sometimes offended people. “Artists must never shrink from a confrontation with society or the state,” he wrote in 2008.

Nor was it too much concern for Elligett, his most recent editor at The Age.

“You wouldn’t say it was one of his KPIs to exactly be in step with what everyone else thought,” he said. “I don’t mind the idea of challenging people every now and then.”

Leunig certainly did that. And he delighted them. And he offered them solace and comfort and the knowledge that they were not alone, no matter how much it sometimes felt that they were.

The world might be crazy and cruel and beyond comprehension, he told us, but it is also a place of infinite joy and beauty. You just need to know where to look.

For 55 years, we looked towards Michael Leunig. And more often than not, we found there precisely what we needed.