Getty Images

Getty ImagesPeople living with perceived misokinesia – a diagnosable hatred of fidgeting – call it “life limiting” and say they’re buoyed by it becoming recognised as a medical condition.

After the BBC’s earlier reporting, many people got in touch to share their own lived experiences, including one woman who said she had “suffered in silence” since childhood.

Researchers have been looking into the annoyance of little habits some of us can’t stand – like tapping a foot, picking fingernails or smoothing down hair.

People often report it overlaps with another more recognised condition called misophonia – an intense dislike of other people’s noises, such as heavy breathing or loud eating.

‘It can be life-limiting at times’

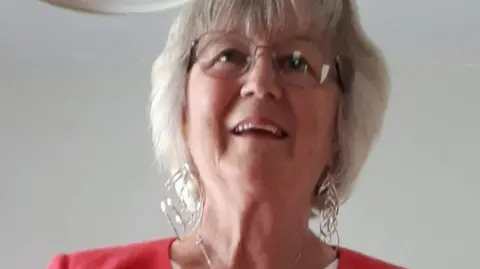

For Annette Guest, 73 and from Worcester, everyday occurrences like someone jiggling their leg could be enough to prompt a reaction.

She said her symptoms began at the age of 13, and followed her into adult life including at work.

“I nearly left a job because someone kept sniffing…thank god they left before me,” she said.

She described the condition as “life-limiting at times”.

“When it’s your close family that cause the triggers, and [it] creates the feelings of anxiety and fight or flight response,” she said.

‘We desperately want to find a cure’

Dawn Page

Dawn PageMany people who contacted the BBC were buoyed by the fact misokinesia was becoming recognised as a condition, and research was being done to better understand it.

Dawn Page from Manchester said she “suffered in silence throughout my childhood”, but has only in the past decade been able to talk about it.

She’s now helping her daughter, who has misokinesia and misophonia.

“We both struggle on a daily basis, however because my daughter is still at school her stress levels are extremely high and she suffers with migraines which I believe is as a direct result of the stress,” she said.

Her daughter has recently been given permission to use noise cancelling headphones to help her focus during exams.

Ms Page also paid for her daughter to get therapy from a leading expert on misophonia, but said it was “ineffective”

“We desperately want to find a cure,” she added.

‘What a load of nonsense, snap out of it’

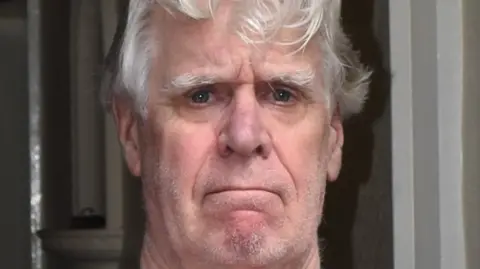

Peter Holmes

Peter HolmesBut managing the condition can be incredibly difficult, something experienced first-hand by Dr Peter Holmes, 72, from Lancaster.

He said he developed misophonia during puberty, and then several years later, misokinesia.

He was triggered by a close family member who would fidget and smooth their hair. That person was also dismissive of his condition, he said.

He recalled the attitude towards him was, “what a load of nonsense, snap out of it”.

“I now understand that my conditions were like a reflex or an allergy, my response was hard-wired and no conscious choice was involved,” he told the BBC.

“These things created a terrible anger in me.”

‘I get very frustrated when I see him do these things’

Wendy Martin

Wendy MartinThe challenges of misokinesia can also be amplified by other conditions.

Wendy Martin, who is 68 and from Oxford, is “profoundly deaf” and uses a hearing aid.

She told the BBC about her thought process when around her husband.

“[He] taps his fingers, drives me mad. I get angry at him. Why does he do this?

“He grabs a corner of the top part of his jumper near his neck. I scream internally.”

She said her deafness make her focus on body language and facial expressions more so than a hearing person does.

“I get very frustrated when I see him do these things.”

‘They are controlling people around them’

Among the people that contacted the BBC were loved ones of those with misokinesia.

Sophie, not her real name, said being around her 32-year-old autistic son who has the condition was akin to “living on eggshells”.

“I really have to watch what I’m doing with my hands. You have to be very still, you have to be really mindful about the way that I’m speaking.

“I have suffered. Even being in the room and breathing triggers him. It is life-limiting.”

She said there needs to be “boundaries” around behavioural adjustments for people with the condition.

“They are controlling people around them,” she said.

“I don’t think we can just say it’s because he’s autistic or he’s got misokinesia and we need to just allow for it”.

She added: “You also have to take a position which is, ‘I have to breathe, you might not like the sound of my breathing but I’d die without it.'”

Sophie said while research into the condition was a good thing, the focus should be on equipping those who have it with “coping strategies”.

“Otherwise it’s just going to be anarchy and chaos out there,” she said.

“Can you imagine being at a restaurant where half the people have all got that condition, it’d really be kicking off wouldn’t it.”

Additional reporting by Amy Walker