Canada has seen many high-profile food recalls this year — from sweet kale chopped-salad kits to plant-based milks — and even some Listeria cases.

Why does it seem like there have been so many recalls recently? Here’s what you need to know.

What’s been happening?

Over the summer, in what may have been the most talked-about recall, three people in Ontario died in a listeriosis outbreak associated with certain Silk and Great Value plant-based beverages. A total of 20 people were also sickened in Quebec, Nova Scotia and Alberta. The affected products included almond milk and oat milk.

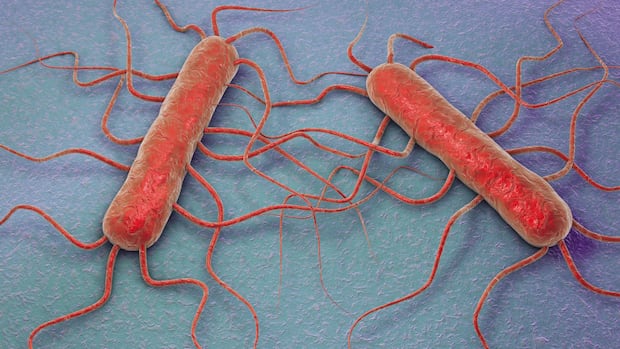

People who eat foods contaminated with Listeria may carry the bacteria and not develop the listeriosis illness. But more severe illness may result in the brain infection meningitis and blood infection in newborns and older adults. Severe illness during pregnancy is also a risk to the fetus.

The Public Health Agency of Canada says a third person has died in a Listeria outbreak connected to Great Value and Silk plant-based milks. The affected products include Silk brand almond milk, coconut milk, almond-coconut milk and oat milk, as well as Great Value brand almond milk with best-before dates up to and including Oct. 4.

Last month, the Public Health Agency of Canada said the outbreak appeared to be over and it closed the investigation.

There was also news coming from McDonald’s in the U.S. of slivered onions tied to E. coli illnesses, and 61 people infected with an outbreak strain of Listeria from 19 U.S. states tied to deli meats.

And over the past few weeks in Canada, recalls have included organic carrots, due to E. coli risk, and cucumbers and chopped kale salads, over salmonella concerns.

Have there been more food recalls than usual?

Not exactly. There have been 139 recalls so far in the 2024-25 fiscal year, which ends March 31, said Meghan Griffin, acting manager of food safety and recalls at the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA).

On average, there have been between 220 to 250 total recalls each fiscal year for the past five years. (There was an outlier in the 2019-2020 year, which saw 560 recalls, according to the CFIA’s data.)

There hasn’t been a significant increase over that period either, says Griffin.

The appearance of an increase might be because the food supply is under scrutiny — and that captures the public’s attention.

“I’m thinking that it’s heightened awareness and more rigorous testing,” said microbiologist Lori Burrows, a biomedical sciences professor at McMaster University. “When some recalls start happening, people start to take a closer look.”

That includes food producers, processors and distributors, as well.

A string of product recalls, including some involving E. coli, Listeria and salmonella, has sparked concerns about food safety. Lawrence Goodridge, director of the Canadian Research Institute for Food Safety at the University of Guelph, says the data doesn’t indicate an increase in recalls but adds the pandemic did cause some disruptions in food safety.

Timothy Lytton, a law professor at Georgia State University, said contamination and outbreaks are identified quicker than before.

“Much of this is a function more of media coverage and public anxiety and the way they feed off each other, rather than particular hard data that we have about how dangerous your lettuce is in the salad tonight.”

Recalls aren’t always because of potential pathogens — they’re also for materials found in food like glass, unlabelled allergens, or because products haven’t been labelled in both English and French.

And not all recalls are triggered because people have gotten sick, said Burrows. Sometimes they’re done by the company pre-emptively, because they spot an issue in routine testing. The recent recalls of carrots and sweet kale salad are examples of this.

Are there different types of recalls?

The CFIA classifies food recalls into classes I, II and III, for high, moderate and low risk that eating the food can lead to health problems, and if so, the severity. Class III also includes products that have no health risk but don’t comply with legislation.

Ian Young, an associate professor in occupational health at Toronto Metropolitan University, said fatal contamination is rare.

Canada has been hit by a number of romaine lettuce recalls. We set out to the U.S., where the majority of our leafy greens come from, to dig up why E. coli outbreaks continue to plague our food supply. We meet one B.C. family whose lives have been forever changed by a contaminated salad.

Young noted that in the case of the listeriosis outbreak in plant-based milk, the CFIA concluded that the Pickering, Ont.-based facility did not properly implement environmental swabbing and finished-product testing.

What is the food industry doing?

Young said farmers should test their irrigation water and compost for signs of fecal contamination from livestock, wildlife or manure, to help reduce pathogens.

Microbiologist Keith Warriner, a food safety professor at the University of Guelph, said new technologies could play a role.

Previously, some foodborne contamination would have flown under the radar, he said. Now, DNA fingerprinting allows investigators to connect a pathogen, such as E. coli O157, that’s causing illnesses to the contaminated product in question, like onions.

The CFIA’s inspections of food processing facilities are prioritized by risk, Warriner said, with deli meat and seafood processors commanding more attention. That could mean nut and plant factories, like the one linked to the plant-based milk contamination, don’t get inspected as often.

Triggers for CFIA investigations include consumer complaints to companies or the agency, and the CFIA’s routine sampling.

When an investigation is warranted, then the CFIA does on-site inspections, checks records to try to identify the source of a health hazard, considers exposure levels and decides whether to recall the product or not.

If so, it follows up to ensure no recalled products remain on store shelves.

What can consumers do?

Mainly pay attention to food recalls, Burrows says.

Proper food handling and prep can also help reduce the risk of infection.

Standard food safety advice includes:

- Clean — Wash hands and surfaces often.

- Separate — Don’t cross-contaminate produce and raw meat.

- Cook — Cook to proper temperatures, checking with a food thermometer.

- Chill — Refrigerate promptly.

The goal is to keep pathogens below the level that will cause disease, she said.

But if there were more recalls, it wouldn’t necessarily be a bad thing.

“I would take [it] as a sign of success actually, that there are more recalls, because that means that those things are getting caught before they make people sick or shortly after.”