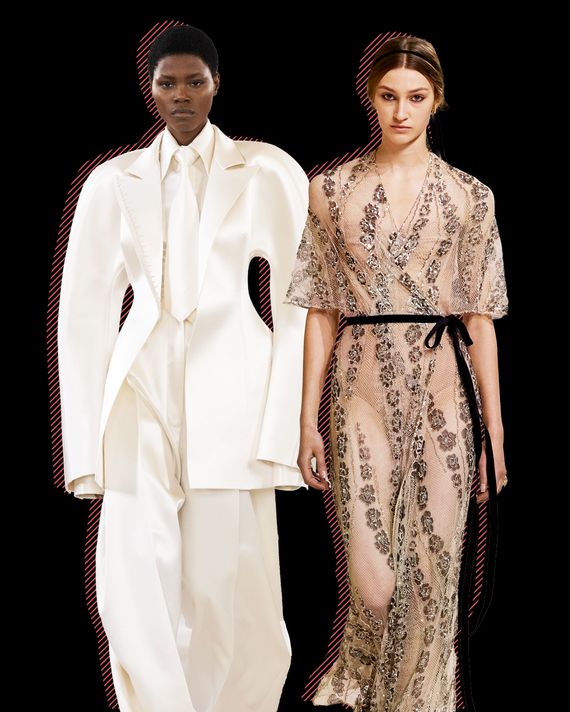

Schiaparelli (L) and Dior (R)

Photo-Illustration: by The Cut; Photos: Courtesy of Schiaparelli, Dior

Daniel Roseberry exhumed Elsa Schiaparelli’s 1936 skeleton dress, leaving the merest trace of bones in a cream-colored bodice and drenching it from the queenly shoulders to the floor in fringe. And since he’s from Texas, and still a boy at heart, Roseberry also alluded in his Schiaparelli collection to horses and cowboys, aliens from outer space, genuine technological artifacts like CDs, and the movies. Saying that much of the show was based on things in his memory, he ended it with the music from Top Gun.

Maria Grazia Chiuri, the women’s creative director of Dior, was doing some excavations of her own. She revisited a 1952 Dior collection, specifically a sculptural dress in silk moiré called La Cigale. Amazingly, Christian Dior’s description of the dress had been preserved, and, he said he wanted to combine a feeling of history with the streamlined aesthetic of the 1950s, namely, planes, trains, and automobiles. So La Cigale was a kind of 17th-century court dress — extending a bit from the hips — but also seemingly engineered for speed. And Chiuri has taken that concept and considered it again in a sublime haute couture collection, on Monday in Paris.

Photo: Courtesy of Dior

For her show, Chiuri invited the artist Isabella Ducrot to adorn the walls with 23 enormous paintings of dresses, mostly historical, some evoking Eastern cultures, and all surrounded by a hazy aura. Ducrot called her installation “Big Aura,” partly in reference to questions that German philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin famously raised in the 1930s about the impact of reproduction on original, one-of-a-kind art. He had in mind photography, essentially asking if the reproduced image causes a loss of aura. And the Dior show notes cited Benjamin, which sounds pretty highfalutin.

Well, lots of designers over the years have drawn on Benjamin — Alessandro Michele, for one — and Benjamin himself wrote a lot about fashion in The Arcades Project, his landmark study of 19th-century French capitalist culture. One of the oddities that intrigued Benjamin was the amount of plush materials, notably velvet, used in homes that could leave a “trace” of a person. It leaves the mark of an individual. That’s perhaps not the same as “aura,” but trace is what you nonetheless experience in the best couture, one of the last crafts made almost entirely by human hands, for individual bodies, and springing from memories and unexpected connections. You sense those elements, in different degrees in a couture garment, you couldn’t really do with a machine made garment, which is produced in the thousands

Roseberry’s Schiaparelli is doggedly and dangerously in that spirit, sometimes pushing things over the edge — perhaps deliberately. Chiuri primarily used cotton, silk velvet, and silk moiré. Moiré has been used for centuries, originally in Asia and then for European royals and clergy. It’s produced on mechanized looms, but the watery effect is achieved by hand. As a result, no two meters of cloth are the same. And today, according to Dior, only one firm in France — Benaud of Lyon — still produces real moiré.

Roseberry, who previously worked at Thom Browne, is talented and curious enough to design for almost any house, and couture has clearly fed his imagination. Backstage on Monday, greeting Jennifer Lopez, he explained that her fluffy, white, flower-petal jacket (with a Lesage-embroidered sunburst on the back) was actually made of real rose petals that had been preserved. Lopez beamed.

Photo: Courtesy of Schiaparelli

But Roseberry’s approach to Schiaparelli has been mainly through fantasy, for better or worse. One of his looks this season is dubbed the “creature” dress because it’s entirely covered with white petals for a scale effect (the model wore a matching balaclava with resin eyelashes and hair). And, as he acknowledged backstage, the brand gets a lot of attention online from people doing AI versions of his designs. That might have spurred him to create pieces that looked embroidered with a small landfill of outdated technology: a dress made of flip phones, motherboards, CDs, as well as an alien robot baby (cradled by a model in rather lovely white cargo pants and an undershirt). But the idea of that kind of embellishment is not really sophisticated. For that matter, AI as designers are generally using it also isn’t interesting. It makes you seem uncool.

Roseberry was far more successful with sculptural and elegant shapes that subtly referenced either Elsa Schiaparelli’s designs or those of other great couturiers, including Cristóbal Balenciaga — for volumes and luscious draping. He said he visited the exhibition at the Palais Galliera of Azzedine Alaïa’s private collection, which is heavy on Balenciaga and Charles James.

Photo: Courtesy of Schiaparelli

Anyway, I loved those trace elements of couture and cowboy alike fleeting through this collection, including his exceptional matador jackets, with hunks of fringe, and an oversize jacket in off-white denim studded with two-inch knobs that resembled dressage braids and stamped near the left shoulder with the word “Schiaparelli,” as if snatched from the label on a dressmaker’s dummy. Shades of Martin Margiela’s famous Stockman collection?

Perhaps. Couture, like music and movies, is a constant echo of ideas and allusions, and Roseberry knows how to play his part.

Once, when I asked Alaïa why he kept working on the same ruching technique — making the gathers smaller, wider, flouncier — he said he did it because he wanted to understand how he might industrialize the process. Couture works in reverse: It can free a designer from computer screens. It puts them in company with others who do originally creative things. It exercises the mind in a different way. It supports the craft tradition as well as a culture. And for the brands that still do couture, like Chanel, Dior, and Valentino, it adds prestige.

Photo: Courtesy of Dior

“I love fashion history,” Chiuri said during a preview at Dior. “And I like a lot the pieces that in my mind are timeless.”

Chiuri had her usual pencil suits with the classic Bar jacket, along with some lovely dresses at the start in cotton khaki. The beauty of this collection, though, lay in the invisible or anyway what would be extremely hard to see in images.

Photo: Courtesy of Dior

For example, she did a sleeveless column in white silk crêpe that was entirely hand-pleated — in all likelihood from a single piece of fabric — and finished with delicate smocking details. She also showed several kimono or wrap dresses, in black crêpe, that were wonderfully simple and elegant. Similarly, there was a beautiful black velvet gown with the hint of a sweetheart neckline and subtle, subtle draping at the hips, and a singular long dress in citron-green velvet with a rolled neckline.

Sometimes Chiuri’s models can look like nuns, but not on Monday. This season also seemed to add far more color, like the deep moiré reds and a bitter yellow on a full-skirted dress embroidered with flowers made of flattened bits of ribbon. The telling sign was in her array of neckline shapes, each as flattering as the next.