Archaeologists have discovered a first-of-its-kind medical prosthesis in Poland: a nearly 300-year-old device that helped a man with cleft palate live more comfortably with this condition.

Nowadays, individuals born with cleft palate can get surgery to fix the condition, which occurs when the roof of the mouth, known as the hard palate, doesn’t completely close during gestation. The hard palate prevents substances in the mouth from entering the nasal cavity, and it also helps with swallowing, breathing and talking, according to the study. Without access to modern surgery, this 18th-century man, who died at around age 50, found another way to deal with the condition: a prosthetic, made of wool and precious metals, that fit into his nasal cavity.

“This is probably the first such discovery not only in Poland but also in Europe,” study first author Anna Spinek, an anthropologist at the Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy in Poland, told Live Science in an email. “No such devices exist in institutional and private collections (Polish and foreign).”

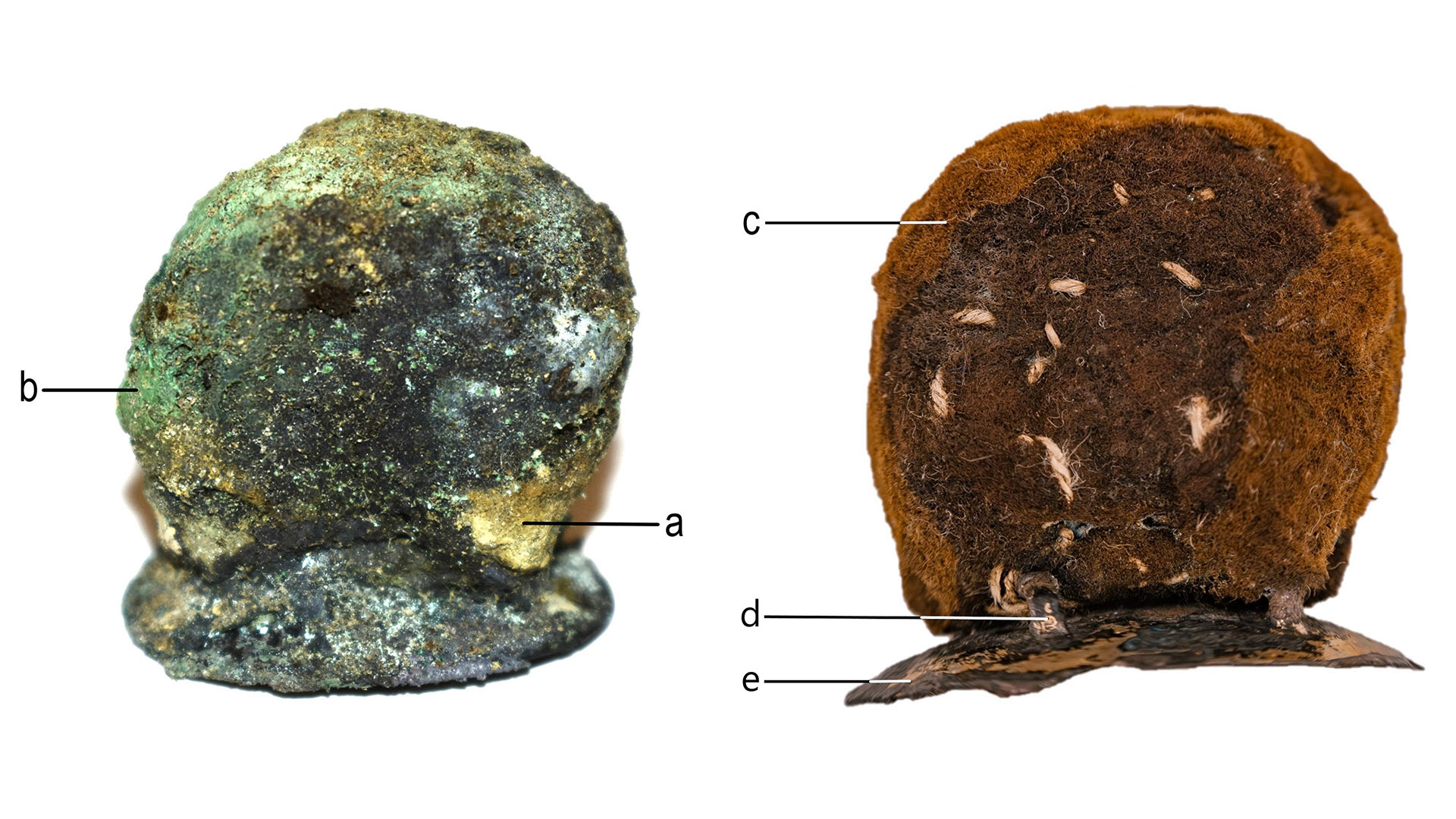

The “exceptional” 1.2-inch-long (3.1 centimeters) prosthesis, known as a palatal obturator, weighs around 0.2 ounce (5.5 grams), according to the study, which was published in the April issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. It comprises a woolen pad sewn to a metallic plate.

The researchers found the prosthesis in a crypt in the Church of St. Francis of Assisi in Krakow during an archaeological excavation from 2017 to 2018. It lay between the jaws of a man who had cleft palate, according to a physical examination and a CT (computed tomography) scan of his remains. When archaeologists removed the prosthesis, they noticed that a fiber pad they later identified as wool bore specks of yellow (probably gold) and green (probably copper), which were unintentionally removed during the conservation process. It’s likely that the wool pad was covered with a thin sheet of copper and then gold to help prevent infections by blocking secretions that could soak into the fabric.

Related: 17th-century Frenchwoman’s ‘innovative’ gold dental work was likely torturous to her teeth

“Today, it is difficult to assess how well the obturator fitted or how tight a seal it provided,” the authors wrote in the study. “However, modern-day patients struggling with similar health problems describe the use of a prosthesis providing improvements in speech (which becomes clearer) and increased comfort when eating.”

To determine the composition of the prosthesis, the researchers analyzed it under a scanning electron microscope, which greatly magnifies the surface of an object, and with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, which analyzes chemical composition of a sample. They found that the metal pieces were largely made of copper, with considerable amounts of gold and silver. The wool bore traces of silver iodide, which might have been added for its antimicrobial properties.

Orofacial clefts, which include cleft palate and cleft lip, have a global prevalence of 1 in 1,000 to 1,500 births in modern times and have been known since historical times. The Greek orator Demosthenes (384 to 322 B.C.) is reported to have had cleft palate and is speculated to have used pebbles to fill the gap, the study’s authors wrote. Several works in the 16th century suggest using combinations of cotton, wax, gold, silver, wool and sponges to patch an orofacial cleft. These rare devices were unique and custom-made by dentists. Because they were crafted from precious metals, only people from the wealthiest social classes could afford the devices, Spinek said.

“This research contributes to a better understanding of the evolution of human medical practices in the past, particularly how developmental defects were managed to improve quality of life for individuals,” James Watson, a professor of anthropology at the University of Arizona, told Live Science in an email. He didn’t know of any other premodern burials with similar prosthetics.

“The precision of the prosthesis indicates great craftsmanship,” study co-author Marta Kurek, an anthropologist at the University of Lodz in Poland, told Live Science in an email. She highlighted that the prosthesis is made of highly thin metals that are delicate and not as easy to work with as modern materials, and yet it was perfectly adapted to the defect.