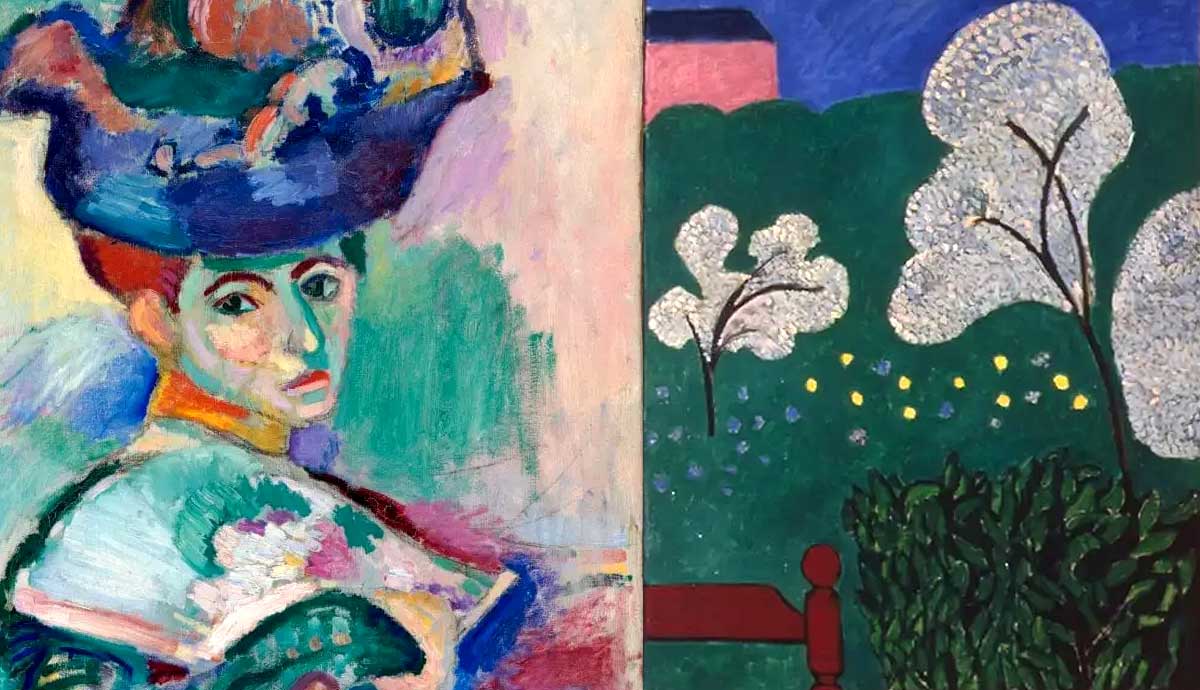

Fauvism was a pivotal art movement of the early 20th century, spanning roughly 1905 to 1910, in which artists began experimenting freely with heightened, unnatural colors and wild, painterly brushstrokes. Artists including Andre Derain, Henri Matisse, and Maurice de Vlaminck broke new ground in a European world used to seeing representational art, thus paving the way for the abstraction and expressionism that followed. While these three were the leading forces of the movement, various other artists came to emulate similar styles and approaches.

The group’s name, as coined by the art critic Louis Vauxcelles, meant “the Wild Beasts,” a nod towards the chaotic colors and free brush marks that we now recognize as a hallmark feature of Fauvism. We take a closer look at the main aims of the radical art movement that helped usher in the individualistic nature of the modernist era.

To Separate Color From Representation

Fauvism’s most definitive goal was to separate color from the depiction of reality. Instead, artists played with how color could become an independent force of its own free will, with the ability to express something within the artist’s inner psyche. Artists deliberately worked with crude, raw colors, sometimes straight from the tube, to create noisy, clanging visual effects. They often deviated from reality, painting red trees and orange skies, for example, and combined a riotous blend of clashing hues that were aimed to have as striking a visual impact as possible.

Maurice de Vlaminck and Andre Derain became friends in 1901 and worked closely side by side in a shared studio near Paris to develop this bold new approach. Meanwhile, Matisse had already befriended Derain in 1899, and he met De Vlaminck through this friendship. While these three artists were the pioneers who began the movement, others followed in their path, including Roaul Dufy, Georges Rouault, and Othon Friesz.

Simplified, Flattened Designs

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

Because the Fauvists were so preoccupied with color, they placed less emphasis on their choice of subject matter than the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists before them. This meant they chose simple, traditional subjects such as portraits, landscapes and interiors, which they could then rework in a series of experimental and imaginative ways. Often Fauvists deliberately simplified their subjects through flattened designs and cropped compositions, and this gave them room to play freely with deconstructed visual effects.

Artists would frequently design their composition around the placement of color rather than real observation of the world around them, and it was this approach that paved the way for the more abstract languages that were to come.

Individual Visual Languages

Rather than having a ‘house style’ as is seen in certain art movements, the Fauvists each developed their own highly distinctive visual languages which emphasized imagination, creativity, and self-expression. Matisse began his career as a Fauvist before moving through a series of stylistic variations, but large areas of flat, decorative color and pattern were a recurring theme, often outlined with fluid lines. De Vlaminck expanded on the dappled brushstrokes of Impressionism and Post Impressionism, taking them to daring new heights with larger brush marks and saturated color. Meanwhile Derain’s ambient, vivid colors were aimed at expressing his inner states of mind, as he wrote, “color [is] a means of expressing my emotion and not just… a transcription of nature.”

A More Subjective Approach to Making Art

One of the most important goals of Fauvism was to change art from being a representational tool into a means of expressing the artist’s individuality. While this might seem commonplace today, in the context of the early 20th century, art had primarily been a means of telling stories or depicting people and places from the real world. Impressionist and Post Impressionist artists undoubtedly played a role in divorcing art from reality, but the Fauvists took this approach and ran with it, delving further than ever before into the realms of artistic freedom and self-expression.

By Rosie LessoManaging Editor & CuratorRosie has produced writing for a wide range of arts organizations including Tate Modern, The National Galleries of Scotland, Art Monthly and Scottish Art News. She holds an MA in Contemporary Art Theory from the University of Edinburgh and a BA in Fine Art from Edinburgh College of Art. Previously she has worked in both curatorial and educational roles, discovering how stories and history can enrich our experience of art.